Society's open secret

French economist Thomas Piketty is on the edge of a major discovery that would transform social life — a breakthrough that was already made a century ago, but was completely ignored.

In our struggle to understand and transform society, we try to separate the signal from the noise. What’s important here? What’s the bigger picture? We look for narratives. We tell each other stories. We explain about the struggle between the rich and the poor. Or describe the loss of faith. Or the clash of racial and ethnic groups. Or the falling apart of the family and the collapse of social norms.

There are countless stories to tell and, for the most part, they all have a grain of truth. But they also don’t hold together so well because they’re single threads in a bigger story that hasn’t yet been told — the story of society itself.

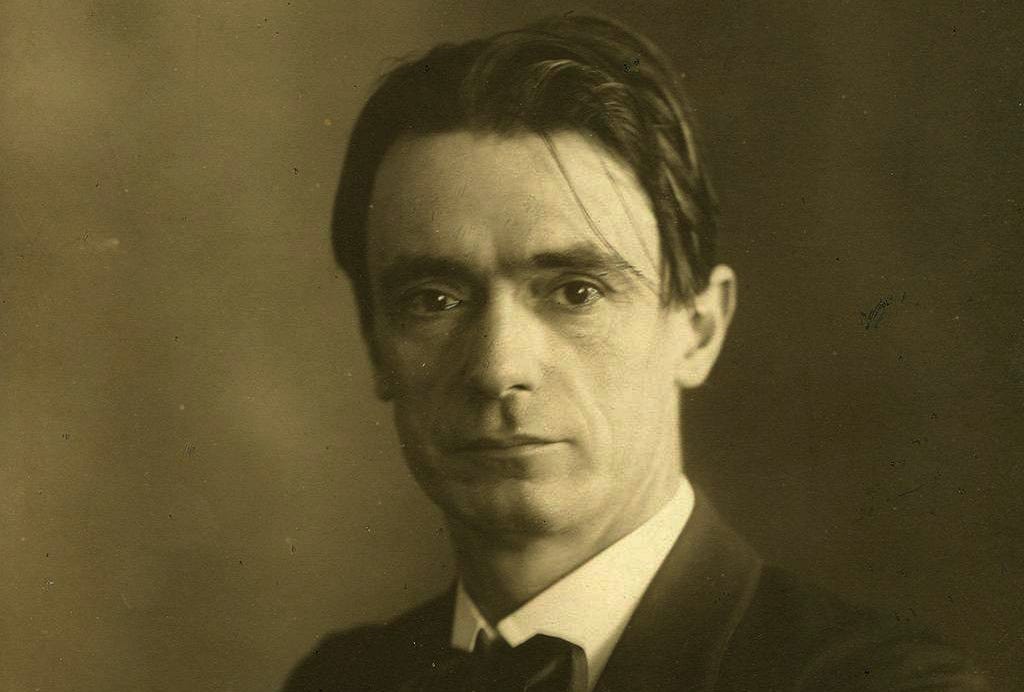

This story actually has been told, but chances are you’ve never heard it. A century ago the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner wrote and lectured extensively about it in the aftermath of World War I. He spoke about society’s own nature, a lawfulness that could be observed everywhere in social life (throughout human evolution, right into the present day) — a pattern hidden in plain sight.

But Steiner was a meditant and “spiritualist” and was largely dismissed in academic circles. Nonetheless, over the years others have made similar observations in the fields of anthropology, sociology, and philosophy — never with the same power and scope as Steiner, but in the same direction. And now Thomas Piketty, who some have called the “world’s most famous economist,” has also struck upon the same ground in his newest book Capital and Ideology.

This story, the story of society’s integral nature, is essential for us to understand if we want to transform society in a meaningful way. Like a doctor, we have to understand the body social if we want to restore it to health. So here’s a sketch — a description of what Piketty describes and a few additional pictures by Steiner to point to its fuller significance.

The first thing to mention about Piketty’s Capital and Ideology is its sheer breadth. The book is encyclopedic, a scholarly tome that covers the history of global society over the last 500-1000 years (and at times reaches still farther back).

Piketty loves wielding huge data sets and it pays off: after scrutinizing so many societies over so much time, patterns emerge. For instance, he can describe in detail how earlier, premodern societies had remarkably similar social hierarchies that gave society a stable form; and how in modern times these have broken down, replaced by the centralized nation-state (sometimes more democratic, sometimes more authoritarian) and new social hierarchies based solely on property and wealth.

That might sound like a familiar story: we used to obey kings in their castles, but now money is king. But what’s most interesting about Piketty’s telling of this story is the first part, because where we’ve come from — if we’re able to see it rightly — can actually tell us a whole lot about where we’re going.

The pattern that Piketty sees in earlier societies is what he calls “ternary” or “trifunctional” — that is, that they were comprised of three main groups or classes. These were priests, warriors, and workers. Here’s how Piketty describes it:

“The simplest type of ternary society comprised three distinct social groups, each of which fulfilled an essential function of service to the community. There were the clergy, the nobility, and the third estate. The clergy was the religious and intellectual class. It was responsible for the spiritual leadership of the community, its values and education; it made sense of the community’s history and future by providing necessary moral and intellectual norms and guideposts. The nobility was the military class. With its arms it provided security, protection, and stability, thus sparing the community the scourge of permanent chaos and uncontrolled violence. The third estate, the common people, did the work. Peasants, artisans, and merchants provided the food and clothing that allowed the entire community to thrive. Because each of these three groups fulfilled a specific function, ternary society can also be called trifunctional society…

“The same general type of social organization could be found not only throughout Christian Europe down to the time of the French revolution but also, in one form or another, in many non-European societies and in most religions, including Hinduism and both Shi’a and Sunni Islam… The ternary pattern can be found in nearly all premodern societies throughout the world, including China and Japan.”

What’s going on here? Why would the same basic type of social organization be found all over the world? The key to this question can be found in the form itself, so let’s take a closer look.

The idea of a tripartite (three-part) social organization was first popularized in academia by the mythographer Georges Dumézil in his 1929 book Flamen-Brahman, and was soon embraced by a number of other prominent scholars (most notably Mircea Eliade and Claude Lévi-Strauss).

As a mythographer, Dumézil dealt with the far distant past, with prehistory. His study of the myths and sacred texts of early proto-Indo-European peoples led him to propose what he called the trifunctional hypothesis, the idea of a class or caste structure based on a common tripartite ideology that represented three main social functions: the sacral, the martial, and the economic. (Basically, those who tend to the sacred, those who look after security, and those who produce.)

For instance, the origin story of the ancient Scythians tells of the skyfather Papaios giving four gifts corresponding to these three main functions: the chalice (sacral), the battle axe (martial), and the yoke and plow (economic). Turning to ancient Greece, we find these functions again in Plato’s Republic where the ideal city-state is described as being ruled by a philosopher-king (sacral), protected by a guardian class (martial), and fed by the citizens (economic).

But it’s not only in the realm of myth and philosophy where we find this trifunctional ideology expressed, it also took concrete organizational form throughout the world (albeit in significantly different ways).

In the medieval world of European Christendom, we see the ternary structure quite clearly in the way social life was organized as a society of orders: “those who pray” (oratores), “those who fight” (bellatores), and “those who work” (laboratores).

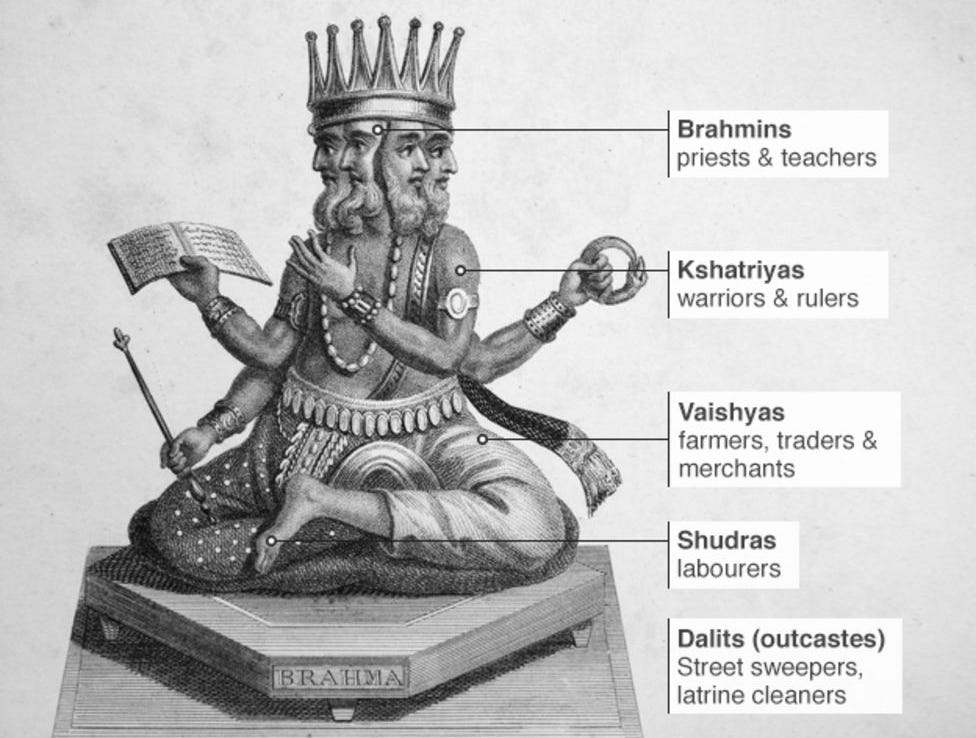

Within the Hindu caste system of India, we generally think of four main castes (with thousands of subcastes, as well as dalits, or “untouchables,” outside the caste system). But on closer examination we again find the trifunctional division with the first two castes acting as priests and warriors, and the last two castes (as well as the dalits) fulfilling the economic function.

Such divisions are everywhere, and Capital and Ideology is a global tour — through China and Japan, Iraq and Iran — with Piketty as guide, pointing out the variations of the ternary form as it manifests through the ages and in each country’s unique history.

But the ternary class structure, for all its regularity and stability, couldn’t last forever. As it began to break down in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, we find transitional political forms arising, forms that appear more democratic and classless but are still imbued with the old trifunctional ideology.

In England, for instance, we find the parliament divided into only two houses — the House of Commons and the House of Lords — but still manifesting the trifunctional schema, with the first house representing the commoners and the second house representing the clergy and nobility (the “lords spiritual” and “lords temporal”). In Sweden, we find the parliament divided into four — nobility, clergy, urban bourgeoisie, and landowning peasants — but again, the last two are only different subgroups of the productive class.

In many ways, the transition away from ternary society was gradual, as monarchies grew more centralized and power consolidated in fewer and fewer hands. Here’s how Piketty describes it:

“Once the centralized state can guarantee the security of people and goods throughout a sizable territory by mobilizing its own administrative personnel (police, soldiers, and officials) without drawing on the old warrior nobility, the legitimacy of the nobility as the guarantor of order and security will obviously be greatly diminished. By the same token, once civil institutions, schools, and universities capable of educating individuals and producing new knowledge and wisdom come into being under the aegis of new networks of teachers, intellectuals, physicians, scientists, and philosophers without ties to the old clerical class, the legitimacy of the clergy as the spiritual guide of the community will also be seriously impaired.”

In the end, though, trifunctional society wasn’t just overturned because life became more complex and specialized, but because humanity outgrew it. It was too rigid, too limiting. The human need for social mobility — to be able to exercise one’s full capacities regardless of what class one’s born into — became ever greater, while the excesses of the upper classes and indignities suffered by the lower class became ever more unbearable.

Nowhere was this perhaps more the case than in France, where the commoners had already tasted the possibility of political power with the establishment of the Estates General in 1302, only to see it taken away in subsequent centuries and replaced by the worst forms of despotism. When Louis the Great, also known as the “Sun King,” pronounced “L’état, c’est moi” (“I am the state”), one can sense the end of an era approaching. As it says in Proverbs: pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall.

And so, beginning in 1789, the commoners rose up. The French revolution would change not only the face of France, but eventually of Europe and the world, spelling the end of the old society of orders. The cry for “liberté! égalité! fraternité!” — for freedom, equality, and brotherhood to live between us all — rang out. And was followed by the seemingly impossible task of figuring out how to organize society anew.

Now that we’ve reviewed the history, let’s return to the original question, Why was this form of social organization so prevalent in premodern times? Perhaps it’s obvious by now: Because these three functions are the functions of society. They constitute the essential nature of society.

To fully understand this, we should update and expand how we see these functions in today’s world. Luckily, we can build the bridge to our own time starting with Piketty’s description of the gradually diminishing role of clergy and nobility, quoted above.

We see, for instance, the ancient warrior class transform over time. Where previously the lord of the manor protected his people from outlaws and contending rulers, that function fell more and more on the king. The monarchy became a “centralized state… mobilizing its own administrative personnel (police, soldiers, and officials).” Those who were once the warriors of the land — the “nobles of the sword” (noblesse d’épée) — no longer wielded the sword, but now simply inherited their positions and titles. They were replaced by magistrates, ministers, and jurists of the state — the “nobles of the robe” (noblesse de robe). Basically, they were replaced by politicians and bureaucrats.

So we see this function of security taken over by the state with its police and armies. But this function is also greater than just security, it’s governance in general — it resolves disputes, decrees laws, ensures justice. And as the state evolves towards democracy, this function becomes increasingly self-governance.

In Piketty’s telling, the priestly class is also replaced, this time by “new networks of teachers, intellectuals, physicians, scientists, and philosophers,” which points to the fact that the clerical class had originally been all of these things. Part of their function was strictly religious, but they also served the nobility as scribes, counselors, ambassadors, and accountants. They were the “men of learning” — there were no others. They were the first scientists, doctors, and artists (the above illustration of a cleric, knight, and peasant was almost certainly made by a monk). They were the first philosophers and educators. All teaching was, at first, spiritual teaching.

So we see that this function really has to do with the life of the mind more generally. It’s the realm of knowledge and its main task is simply human development — education in the broadest sense. What else are religion, art, and science for, but to grow the human soul?

The third function is the most well-known today, and also the only one Dumézil gave a contemporary name for — the economic function. In earlier times, this would have been largely agricultural, as most people would have spent their days farming, but it was also hunting, gathering, mining, and forestry. Over time, as cities emerged, we see the rise of independent craftspeople and merchants. As the world opens up through trade, and with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, we see manufacturing, business, banking, and the like, all begin to take center stage in human society. Economic activity becomes the main activity. Money becomes king.

So we see that these three functions of governance, education, and economics are still obviously with us today — they’re still the functions of society. What else is there? They cover everything, from the most inner aspects of society (cultivating knowledge) to the most outer (transforming nature into food, shelter, and clothing), and to that which is between (trying to live together in peace).

(It’s worth noting the symmetry and harmony — and, dare I say, beauty — of these functions. In premodern times, a person would likely never have described them in terms of inner and outer, but of up and down — of human beings standing between heaven and earth, reaching up with their thoughts, down with their actions, and outwards towards each other. But of course there are probably countless ways to understand them.)

Coming back to the present, it’s a bit too narrow to still call these functions the sacral, martial, and economic (or agricultural). It points too strongly to their origins and fails to show them in their present-day form. For this, we’re better off following Rudolf Steiner’s lead, who often referred to them as the cultural, political, and economic.

So we find these three functions are still with us and will always be with us — they’re inherent to us — but their outer forms change because we change. At one point we were able to fulfill them through splitting society into classes and castes, but today we can’t stand for this. Today every person must have the opportunity to develop their gifts through education, to give their gifts through work, and to have a say in their government. We no longer belong to just one sphere; we belong to all three.

At this point though, I should admit we’ve somehow lost Piketty. He was with us right until the last minute, helping us bridge to the present day by showing how these functions evolved, but for some reason he never crosses that bridge. In Capital and Ideology he never transitions to talking about these functions today — he doesn’t see how significant it is that they’re continuous — and it’s hard to understand why. It seems part of a bigger blind spot among social scientists: that they can’t recognize society has its own nature, that it’s more like an organism we have to work with, than a machine we can manipulate however we want.

For instance, in describing ternary society, Piketty mentions the theory that it spread from a “single origin.” Piketty dismisses this notion because it’s simply too universal, but he never provides an alternative, he never explains why we find it everywhere.

“At one time anthropologists believed that the ‘tripartite’ social systems found in Europe and India had a common Indo-European origin, traces of which could be seen in mythology and language. More recent theories, still incomplete, suggest that tripartite social organization is actually far more general, thus casting doubt on the old idea of a single origin.”

But what does the “single origin” theory even mean? It means generations of scholars have assumed this social structure was not natural, but some sort of “good idea” that one society had and others copied. To think this you’d either have to believe these functions were invented out of thin air (“I’ve got an idea: let’s feed, protect, and educate our people”) or that there were other vital functions that societies could have chosen, but didn’t. But if so, what are they?

The idea that these functions are inherent to society really isn’t radical. It’s obvious. What’s bizarre is that we have such an estranged and artificial understanding of social life that almost no one has hit upon it. That is, besides Rudolf Steiner.

For the last leg of this journey, then, let’s take Steiner as our guide and try to grasp some of the implications of what it means to live in a society with its own nature, its own lawfulness. What follows has been born from his work.

The fact that society has its own nature means we have to work with it. We can’t just do whatever we want and hope to get good results. We have to understand what makes society healthy and what makes it sick, which begs the question: How should we work with society’s three functions today? How should we organize and direct them?

As we’ve seen, we’ve invested greater and greater power in the centralized state over the last few centuries — should we just continue in that direction? Should we let government direct all three functions, make everything political and just let it all be decided democratically?

It might be tempting to do so, but it would spell ruin for society at large. These functions are radically different from one another — simply imagine a priest performing a rite, a warrior fighting in battle, or a farmer planting a crop. They require different capacities, different expertise. You can’t just interchange them (have the priest direct the farmer, or the warrior direct the priest) and hope they’re still fruitful for society.

Instead we have to let them operate with a certain degree of independence. Which means: we have to learn to see where they rightfully overlap and where they don’t. For example, the government’s laws permeate all of society’s activities, including the economic and cultural, but that doesn’t mean politicians should have a hand in running industry or deciding what’s taught in schools. To do so is to drain these functions of their vitality.

Perhaps Steiner’s most important contribution is his observation of what drives the cultural, political, and economic functions today.

At the turning point of history, when humanity was finally moving from the premodern to the modern era, it cried out for what it most desired, but didn’t yet know how to realize. We cried out for liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Scholars would later mock these ideals as hopelessly contradictory — to want everyone to be equal is to want them to be the same, so you can’t also want them to be different, to be free to be themselves! But enough with the shortsightedness of scholars! What do these ideals really signify?

When we speak of freedom in society, we primarily mean freedom of thought. We want to follow our own conscience, to believe what we believe, and be able to discuss it freely. And so we enshrine such freedoms — of speech, belief, and assembly — as the highest principles in our constitutions.

When we speak about equality we primarily mean equality before the law. We should have an equal say in the government and be treated equally in the courts. (We certainly don’t talk about it in terms of having equal thoughts or equal work.)

And when we speak of fraternity, or what we could call solidarity, we’re simply talking about taking care of one another. We use this concept most often in terms of “worker solidarity” — we long to work together to make sure everyone’s needs are met. (And again, we don’t generally talk about solidarity in ideas or solidarity before the law.)

These three ideals have always been there, pointing the way to the kind of properly differentiated society our hearts truly desire. We yearn for a cultural life where freedom can be realized, where every human being can develop themselves fully and where, as John Steinbeck says, the mind can “take any direction it wishes, undirected.” And we yearn for a political life where equality can be realized, not just in terms of how society treats us, but how we actually experience the dignity of one another. And we yearn for an economic life where solidarity can be realized, where we don’t burn through the planet because of a desperate hunger for more, but where everyone has enough.

When we overturned the old society of orders, we did so because we outgrew it and because it had grown corrupt. Priests and warriors no longer fulfilled their original functions so the social structure was a lie, an empty husk. It was also no longer social — people just leveraged their positions to pursue their own gain. But we didn’t turn society on its head so that every human being could pursue their own gain, so that we too could doggedly chase after prestige, power, and wealth. That wasn’t what inspired us. Instead, we dreamed of a society where freedom, equality, and solidarity could live between us all.

This is the story of society we need today — a story that makes sense of how we got here and points to where we need to go, a story that has all the other stories within it. Because in this story we can see how the privileges of the upper classes evolved, and how a true solidarity will rectify them. How cultures and ethnicities have clashed for millennia, and how true freedom will make a place for them all. How the individual has burst the bonds not only of class, but of all social norms, even of family. And how we can’t simply accept the structures we’re born into anymore, but have to understand and create them for ourselves.

We’ll need a name for this new society we’re creating. We could call it a “modern integrated ternary society,” but that doesn’t really roll off the tongue. I’d recommend we call it what Steiner called it: a threefold society (and the work of restoring it to health, social threefolding).

Academics such as Piketty are working to understand and tell this story, and it’s wonderful they are. But we also need to start telling it. It’s a story that involves us all — we can’t just leave it to academics and policy makers. Instead, we need to strive to understand the nature of society, how these functions should be expressed and differentiated today (how money, property, work, and every other aspect of social life need to be reframed with this understanding). We need to stoke the fire so that freedom, equality, and solidarity burn in us, leaving us no peace till we build them a proper home. Because if we don’t, if we keep violating society’s true nature — manipulating it for our own self-interest — soon there may be no home left.

In the end, all our actions contribute to the health or illness of society, though it’s often incredibly difficult to see how. But still, this is our task: to find the place where we can serve the whole; to give ourselves to what’s always right in front of us — society’s open secret, the wisdom and pattern of our social life that’s hidden in plain sight.

Really great work, Seth! Will share. It´s timeless.

So helpful to see the three functions of society over long ages and many cultures! Thanks very much for connecting this and succinctly describing Piketty's work. You are making the case that social threefolding is not radical at all; it is "merely" conscious.