A democracy Gandhi would respect

Current democracy reform efforts, such as H.R 1, are vital tools of transformation, but they still lack a key ingredient — a path to "experiential" democracy.

“Evolution of democracy is not possible if we are not prepared to hear the other side. We shut the doors of reason when we refuse to listen to our opponents or, having listened, make fun of them. If intolerance becomes a habit, we run the risk of missing the truth.” — Gandhi

This article is about a fundamental aspect of democracy that’s missing from our current debate. Without it, our democracy won’t last, at least not in the long run. That might sound melodramatic, but I think it’s true.

I always planned to weave Gandhi into this article because he touched on this aspect of democracy in his own work, but as I wrote I found myself more and more focused on him. In looking at the pragmatic “reality” of our politics today, I couldn’t help but be ashamed in imagining what Gandhi would think. And in describing the direction that needs to be developed, I wondered if he’d agree. So over time this article naturally became a kind of conversation with him.

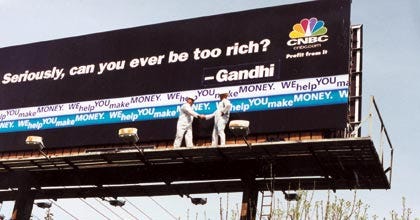

And then I remembered a picture I saw maybe 10 or 15 years ago. It was a photo of a billboard with a very simple message: “Seriously, can you ever be too rich?” It was advertising the business channel CNBC and, though it might sound crude, I imagine a lot of people drove past that billboard and thought, “Yeah, that’s true. You can’t be too rich. We’re all just working to get ahead… That’s a fact.”

That is, until someone climbed up and changed it. Because the billboard was eventually spoofed by some activists to make it look like Gandhi had said it: “Seriously, can you ever be too rich? — Gandhi.” Which is AMAZING. Imagine driving past it after that. Imagine you agreed with it before, but now you saw Gandhi’s name up there. You would know it was ridiculous. Gandhi would never say it.

And in that moment Gandhi evokes one’s own conscience — the small, quiet voice in each of us that wants to do right, that wants to serve the world and not just ourselves. And in that moment our own monstrous and petty greed simply wilts.

That’s what I want to do with this article. I want to take our current democratic practices and ask, Are these moral? And I want to look at the various proposals for reform and ask, Are these sufficient? One way of doing so is simply by asking, Would Gandhi respect them? Let’s find out.

H.R. 1 AND THE STATE OF OUR DEMOCRACY

In the last couple years, the struggle for political reform got a second wind. After years where almost nothing moved on this issue, the Democratic Party finally did something bold: they took up the suggestions of democracy reform advocates and created a massive (almost 900 page) bill — the For the People Act.

The new bill is a veritable wish list of reforms. It expands voting rights, limits gerrymandering, and creates new ethics requirements. It also reduces the influence of corporate money on politics by making “dark money” (where the source of the donation isn’t disclosed) more transparent and by matching small, individual donations at a 6-1 ratio (so for every $1 you donate — up to $200 — the government would kick in an additional $6).

And so, upon winning back the presidency and taking both houses of Congress last year, the Democrats were ready. The For the People Act was the first bill passed in the House of Representatives (which is why it’s also known as H.R. 1) and the first bill sent to the Senate.

For once, it looked like some sort of reform might actually happen.

But then, just in the last month, the bill stalled in the Senate when Republicans filibustered it, refusing even to discuss it. Why do Republicans oppose it? Is it simply partisanship, or do they have justified concerns?

At the top of the Republican list of concerns is voter fraud, an issue that’s still front and center for many conservatives after the last presidential election. They say the bill’s expansion of voting rights would lead to greater fraud by bypassing state laws requiring photo IDs (which Democrats say disproportionately hurt minority turnout), allowing ex-felons to vote, and automatically registering people to vote when they interact with government agencies. Here’s Kevin McCarthy, the House Minority Leader, describing this last point:

“HR1 would weaken the security of our elections and make it harder to protect against voter fraud. Here’s how: It would automatically register voters from DMV and other government databases. Voting is a right, not a mandate.”

Perhaps the most telling part of the Republican’s response, though, is that the alternative bill they put forward in the House — the VOTER ID Act — only addresses election security and doesn’t touch any other issues. The majority of Republican politicians clearly don’t think that money in politics is a problem (though there are exceptions — most notably Matt Gaetz, as was depicted in the 2020 documentary The Swamp).

Those are some of the Republican’s so-called “justified concerns” but what about plain old partisanship?

This is, in fact, likely the main reason they’re against it. Time and again they’ve called the bill a “power grab” by Democrats, in effect admitting their main grievance is that it would give Democrats more power. Which it likely would. Why? Because Democrats tend to be younger, more diverse, and from the city, and it’s a lot of these folks that need the most help navigating the system.

So do Republicans really not want Americans to vote? Yes, if it means their side is less likely to win elections. A lawyer for the Republican National Convention (RNC) actually said this in a recent Supreme Court case looking at the legality of certain voting restrictions in Arizona. One such restriction is the discarding of ballots cast in the wrong district. When one of the justices, Amy Coney Barrett, asked the RNC lawyer why they were fighting to keep such a restriction on the books, the lawyer responded that removing it (and so counting those ballots) would help Democrats and hurt Republicans.

The RNC doesn’t care that people’s votes will be lost. They just want to win.

But, of course, on the other side we have to ask if the Democrat’s new found passion for political reform is the real thing? Because it seems likely that it is a power-grab by Democrats, at least partially — that some of them are probably only pushing this bill for the same reason Republicans are objecting to it: because they want their side to win. That might sound cynical, but what if the tables were turned and the bill would lead to an influx of new Republican voters? Is it likely every single Democrat would still be pushing it? Is it likely it would be on the table at all?

In our struggle for a fair and equal democracy, this should give us pause. On the one hand, it’s obvious: people are in it to win. That’s the game. But when the ideal of democracy takes a back seat to winning, we should ask what such a victory would even look like? If democracy isn’t its own goal, what is the goal?

In my last article, I referred to some of the ways corporate special interests twist democracy so its goal becomes the protection of wealth and privilege. But money isn’t our only “special interest.” We want to see our values win the day, our people get into positions of power. And we really, really, really want to crush our enemies.

So imagine H.R 1 did pass, the grip of corporate power in Washington was weakened, and many more people ended up voting in coming years. Would it lessen the partisanship and the hate?

“A [proponent of democracy] must be utterly selfless. He must think and dream not in terms of self or party but only of democracy. Only then does he acquire the right of civil disobedience.” — Gandhi

GANDHI REJECTS THE QUID PRO QUO

Of course, we do need to put our democracy back in the hands of its citizens, but we also need to ask, What kind of democracy is it? Yes, democracy is about asserting our rights, but those rights are always in relation to everyone else (if we demand a bigger slice of the pie, then there’s less for everyone else). If we never get beyond our rights, our interests, then we’ll never realize the promise of democracy. Because it’s not really about my rights or your rights, but about what’s right.

Gandhi came to this understanding in the course of his own life. In a scene from his autobiography, he describes attending a joint congress of Hindus and Muslims where the main question was about an injustice the Muslims suffered at the hands of the British, and whether the Hindus should support them in seeking redress.

The Hindus saw an opportunity in this: they wanted the Muslims to stop slaughtering cows (an animal they hold sacred), so why not ask them to ban the practice in exchange for Hindu support? It was a quid pro quo — a favor for a favor — the very stuff of everyday transactional politics.

Gandhi disagreed. He argued instead that the Hindus should weigh the question of supporting the Muslims on its own merits. What is fair and just in this situation? The question of cow slaughter should then be taken up at a different time and weighed on its own merits.

The outer difference is subtle, but the inner difference is vast. In the first scenario, the Hindus would decide based on their own interests, on what they wanted. In the second scenario, they would let the moral reality of the situation itself guide them.

In the end, the Hindu faction came round to Gandhi’s viewpoint.

BECOMING SELFLESS THROUGH EXPERIENTIAL DEMOCRACY

Many of the reforms found in H.R. 1 are needed, but they’re not the only changes we need. Yes, we must find the will to eliminate corruption from the political process, but to safeguard against future corruption and not consume ourselves in partisan rancor we need to do more.

It’s not that we need to add something to democracy, but to deepen it, to essentialize it, to make its promise real. Because the true benefit of democracy isn’t just that it gives us a fair playing field to assert our rights, but that it awakens us to the fundamental equality of others.

If there’s a positive good to democracy itself, it’s the realization — the making real — of equality. We usually understand this only in its outer aspect: when we fight for an equal voice in government, or equal treatment before the law, or equal opportunities in life, we’re fighting for fair social systems. We want to be able to go about our life and not be at a disadvantage relative to other people.

This is incredibly important, but it’s not the only aspect of equality. There’s also the experience of equality.

Democracy isn’t just about creating fair systems, it’s also about coming to really know, to experience, other people as equals. This is unfortunately a rare occurrence, so it can be hard to pinpoint, but we can take Gandhi’s example as a starting point: when Hindus and Muslims sat at the same table they could begin to enter into the plight of the other, what they cared about, their concerns and grievances.

To flesh it out further I can give two small examples from my own life:

10 years ago, I spent a few weeks at Occupy Wall Street in Zuccotti Park in NYC. Every night there was a general assembly where hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people would strive to make consensus decisions together. That might sound crazy (and it was — though it was expertly facilitated), but it was also magical. Because every voice mattered. No one would be ignored or steamrolled. Every objection was taken seriously. Everyone was equal. And you could experience it, how people would wake up to their own dignity. Because everywhere else in life we’re always ranking ourselves against each other — I’m better looking than you, better dressed than you, you’re smarter than me, richer than me. These hierarchies are always there, subtle and insidious, but every night in Zuccotti Park they’d fall away and we’d see each other’s basic equality and dignity. It was beautiful. It was exhilarating.

My other experience was jury duty. For years, I did whatever I could to avoid being put on a jury, but then, finally, I was selected. And so I sat for a few days with a group of random strangers and heard the case of someone accused of a crime. And in the process we changed. We became peers — the jury, and also the person on trial. It was clear that our decision was important for this person’s life. We had to pay attention. We stood for the whole community and this person was a member of that community. We had to decide what was just, what was right, for their situation and for the community. It was on us.

What’s the value of such experiences? What would I have missed if I had given up my place at the general assembly or at jury duty, and let someone else represent me? I would never have glimpsed the dawning recognition, the dawning experience, of my fundamental equality with all of these people. This experience is just too muted when we vote for a representative. We need to turn up the volume on it if we want to save our democracy.

The movement for more participatory forms of government is nothing new. Since the Ancient Greeks, we’ve had forms of “direct democracy” where citizens themselves decide on issues and don’t just delegate the task to representatives. Today this is done through proposing new laws (called citizen’s initiatives) and vetoing existing laws (called referendums). Such forms of direct democracy can be found throughout the world, especially in Switzerland, as well as in many U.S. states.

In more recent years, we’ve seen other forms of participation arise under the name of “open democracy” where, for instance, groups of citizens are randomly selected to create new laws or give feedback on existing laws or proposals. One example of this is the “Citizens’ Initiative Review,” which is part of Oregon’s election system and has been piloted in four other states. The review seeks to correct a significant shortcoming of citizen’s initiatives: the flood of advertisements that try to sway public opinion whenever a new initiative is launched. Instead of leaving it to private interests to explain ballot measures, Oregon has instituted a process where a randomly selected group of citizens meet together around the proposed initiative and come up with a more objective statement of key facts for the public.

As one can imagine (as well as see in this video of Oregon’s review process) it’s a powerful experience to directly participate in one’s democracy, even if only in a seemingly small way. But now we need to scale it up: all citizens should be participating in the process of self-governance in some sort of regular, ongoing way.

For many, including Gandhi, this is easiest to imagine at the local level (“In the true democracy of India the unit is the village…. True democracy cannot be worked by twenty men sitting at the center. It has to be worked from below by the people of every village”). I agree, but I think it also needs to happen throughout the political system, all the way up to the level of national politics.

Of course, there would be dangers in making democracy more participatory. Would it clog up the system? What would people do? — Do we even make enough laws to warrant getting everyone involved?

These are justified concerns and we’d have to re-envision the process significantly in order to open it up. But just staying with the citizen’s review process, imagine if we extended it elsewhere. For instance, so much of our legislation is written by lobbyists because “they’re the experts” and “politicians don’t have the time.” But it’s terrible. It’s the most obvious conflict of interest — they just write laws to benefit their industries. Could random groups of citizens, aided by experts, write better laws? Or at least: what if new laws went through a citizen’s review process where the findings were made public and there was a period for public commentary before being voted on? In such a system, the citizens would better know what their representatives were voting on and whose interests were being served.

And that’s just one idea.

THE LIMITS OF DEMOCRACY

But Gandhi would likely take issue with that idea. He wasn’t in favor of the country’s political representatives being a random slice of society — a “large number of… irresponsible men chosen anyhow.” He preferred a small group of moral, upright leaders.

And this points to a larger tension running through Gandhi’s writings on democracy: he worried that the fervor for equality would run roughshod over everything else. Because democracy, misused, can become a kind of religion that destroys excellence. We can say “all people are the same in everything, so all institutions should be run democratically.”

Gandhi wanted people to rise above their prejudice and lower instincts, to form a secular democracy where every individual was recognized for their fundamental equality, regardless of sex, religion, culture, or caste. But he didn’t want to erase these differences outside of politics. He didn’t want democracy to replace religion or any other institution. Because his main concern was the spiritual upliftment of his people and, in this respect, he saw that democracy is spiritually sterile — that it’s incapable of meeting people’s spiritual needs.

“A living faith cannot be manufactured by the rule of the majority.” — Gandhi

But nor should it try. Because there are limits to democracy. Those limits are naturally given to it by its guiding principle: equality. Democratic decision-making should only pertain to those areas where we’re actually equal — to the rights and obligations we all share. To apply it elsewhere is to make a lie of it.

To give the government any hand in other institutions — for instance, in health or educational or economic affairs — is to misuse democracy. Because we’re not equal in deciding what medicine a doctor prescribes, what crop a farmer grows, or what curriculum a teacher teaches. They know these things, we don’t. For us (or our representatives) to get involved in those decisions is to make a mockery of equality and to poison the substance of democracy.

(And, of course, it’s possible for the government to ensure equal access to these things without getting involved and dictating their form — without requiring the same type of education or medicine for every individual. We can have equality of access while preserving both freedom of initiative and freedom of choice.)

The 20th century philosopher Rudolf Steiner described this aspect of democracy in many of his writings. Here’s one way he stated it:

“We must place great value on the following: there must be an area where people truly feel equal to one another. This does not exist currently because, on the one hand, political life has absorbed cultural life, and on the other hand, economic life has been pulled in by political life, so that the state… takes on a position of authority on both sides, and there is consequently no ground upon which responsible people can feel completely equal.”

This is a different understanding of democracy. It’s not just about making laws that can better serve and protect everyone, but about coming to know each other as equals. It’s in this way that we can actually overcome our prejudices and build peace.

But we have to be careful that the ideal of equality doesn’t destroy the freedom of individuals. I’m not talking about the vulgar freedom of dominating others and consuming as much as you can, but the spiritual freedom of developing yourself, thinking your own thoughts, taking your own actions.

Although it’s impossible to say, I believe such a democracy — one that engages its citizens in the actual experience of democracy while preserving the greatest scope possible for the development of individuals — would be a democracy Gandhi would respect.