Rudolf Steiner on building healthy organizations

Understanding the fundamentals of working together — from the school to the factory

Listen to this article | Read this article in Spanish

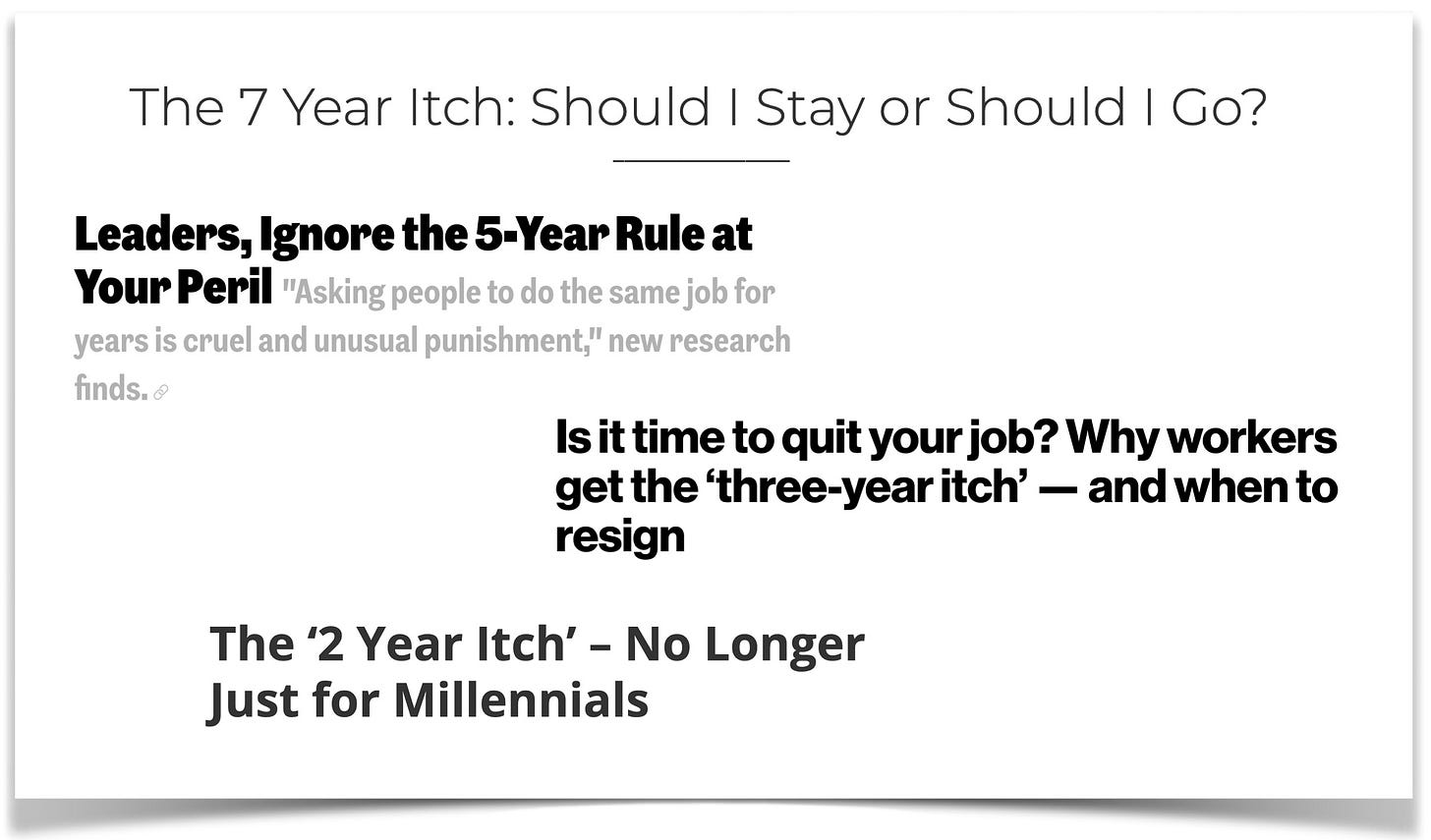

It was once normal for people to work their whole lives at the same job. Today that’s obviously not the case, and not just because technology transforms industries so quickly — our whole way of thinking about work has changed. If today you ask someone how long they’ve worked at a job and they say seven or eight years, they often say it with a sense of embarrassment, like they should have moved on. You can almost hear the voice in their head shaming them: “Is this really all you’re going to do with your life?”

It’s hard for many of us to find satisfaction in our work, but why? Some will say it’s because we’re not doing what we love, but is it really as simple as that? Even when we are doing what we love, there are clearly other factors. For instance, social interactions can easily become toxic, or we don’t have access to the capital we need, or the project gets mired in paperwork, or it just feels ineffectual, like it’s barely scratching the surface of what’s really needed. So how can we work together so that our organization, and the people in it, flourish?

To answer these questions we can look to the 20th century social reformer and spiritual teacher, Rudolf Steiner, who had some of the most penetrating insights into the principles of social life — into how we can work with others in a healthy way. Most of Steiner’s social writings concern the question of transforming society-at-large, and this aspect of his work — how his ideas relate to groups and organizations — has rarely been written about.1

From the start, it would be good to say a word about the end result — what it actually looks like when an organization, and the people in it, flourish.

It does not just look like people reporting higher levels of “job satisfaction” in office surveys. Instead, imagine that a person feels themselves to be entirely in the right place at the right time, and that this realization leads to a “tremendous impulse of all their powers,” so much so that they regard their work as being just as necessary “as in other respects they regard eating and drinking.”2

We know we can’t survive without eating and drinking. Now imagine we felt that way about our work. That it was vital to us. That it nourished us.

Dynamic polarity — the “Motto of the Social Ethic”

One of the most important ways that Steiner describes social health is found in what he called the “Motto of the Social Ethic,” and what others often refer to simply as the “Social Motto”:

The healthy social life is found when, in the mirror of each human soul, the whole community finds its reflection, and when, in the community, the strength of each one is living.3

In this short axiom we have a key for understanding organizations, but we need to unpack it. We will attempt this in a couple ways: by comparing the Motto to similar observations that Steiner made, as well as by looking at some examples of how Steiner worked with organizations — specifically, the Waldorf school and the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory.4

The first thing to say about the Social Motto is that it contains what can be seen as the fundamental polarity of social life: the tension that exists between the individual and the collective, between the freedom of the one, and the harmony of the many.

The fact is, an individual’s self-interest often clashes with the interests of the community — they don’t fit together so easily. So we find different social philosophies tend to favor one or the other: either they champion the community at the expense of the individual, or the individual at the expense of the community.

In the Social Motto, Steiner takes a different tack. He shows how both the individual and the community can only thrive if there’s a certain weaving between them. The community must be consciously carried by its members, it must somehow live in each of them. And the members must also be consciously carried by the community, there has to be a place for them, for their gifts, for their “strength” to find expression. In a sense, it’s an act of mutual recognition — both need to be seen, both need to find a home in each other.

But what does it actually mean for an individual to hold the whole community within themselves? And though we often speak about empowering individuals, what’s really required to do so?

Perceiving the whole

Steiner touches on this first question in a series of essays he wrote from 1905-1906. There he describes how, when people can overcome their self-interest and work together selflessly, the whole community is better off. But how does one do it? Steiner is no mere preacher of morality. He knows how difficult it is to overcome self-interest, so he points to the one thing that can replace it:

If any man works for another, he must find in this other man the reason for his work; and if any man works for the community, he must perceive and feel the meaning and value of this community, and what it is as a living, organic whole.5

Self-interest can’t simply be eradicated, it has to be replaced by a concrete experience of the other. We have to learn to perceive the “meaning and value” of the community, not as a static ideal, but as a living reality.

First example: a factory

Certainly one of the hardest places to do this must be a factory, where the sheer size makes it difficult to wrap one’s mind around the whole undertaking, and where the individual is usually stuck manufacturing some small, seemingly insignificant component — the part of a part of a part. But that also makes it one of the most necessary places to do it. Here’s Steiner again, this time from his basic book on societal transformation, Towards Social Renewal:

In a healthy social organism the worker should not just stand at his machine, concerned only with its operation and nothing else, while the [director] alone knows what becomes of the produced goods. The worker should be fully involved in the whole process, should be aware how his work in producing the goods relates him to the life of society. The company director should regularly make space for discussions, as important to the running of the business as the work itself, so that employer and employee can develop a shared understanding… Such openness and transparency, aiming to develop free and mutual understanding, will also encourage the [director] to run the business in a responsible and properly accountable manner.

Only someone who has no sense for what inner unity with others, arising through a common undertaking, can bring about in the social realm, will regard what I have said as insignificant.6

So Steiner isn’t just talking about the individual worker perceiving the whole, but of a shared understanding, an “inner unity,” developing between all the workers, including management. To do this, workers need to be “fully involved in the whole process,” need to have regular discussions with management, “as important to the running of the business as the work itself” (my emphasis).

In a conversation with a colleague, Steiner described this in more detail, using the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory as an example. Here’s how his colleague later characterized the conversation:

The essential thing — [Steiner] said in effect — was to create for every worker and employee a picture of the whole of his work and also of its place and setting in the world. He started with the situation as it was in the Waldorf-Astoria [cigarette] factory. All the employees, male and female, should be told about all the work done in the other departments. They should also be given a picture of the tobacco plant itself, of the regions where it is cultivated, of the civilization in the countries concerned. Over and above this they should be told about the whole process of the distribution of the finished product and economic and financial factors involved… When anyone who is engaged on some productive work has a picture of the whole process involved, his consciousness is widened and his human interest kindled. He may continue his work in the narrowest of sections, but he feels spiritually linked with all the others. The social connection then becomes real to him and the feeling of detachment is no longer there.

Rudolf Steiner thought that this widening of consciousness might be achieved by means of lectures and introductory courses. Something like a syllabus of production should be worked out for each industrial firm. He also had in mind that the individual workers might be invited to visit other departments of a factory; they could go first as observers and later on be given opportunities for practical participation.7

So we see that it’s this widening of consciousness, this kindling of human interest, that can replace egoism. It’s of course natural for a person to be driven by self-interest — his own needs and desires are often most real to him. It’s only through education and concrete experience that “the social connection then becomes real to him.”

This gives us a clear picture of how to work towards perceiving the whole organization. And the steps it lays out — the creation of a “syllabus of production,” or a syllabus of service — could be developed tomorrow in any organization (perhaps in yours?). But of course, this ongoing education — this weaving together of the workers through courses and regular discussions — will seem to many like a waste of time and money. Steiner replies that this is because they don’t have any “sense for what inner unity with others… can bring about.” They don’t realize how productive people’s work could actually be, if it was truly vital and inspiring to them.

Empowering individuals

But what about the other part of the Social Motto? How can we make it possible for the “strength” of the individual to find its right place?

Steiner speaks in a number of places about the misuse of human capacities — how we run roughshod over people’s talents and gifts. All of society depends on those capacities; if we don’t utilize what people have to offer, then we’re all the poorer because of it. It’s as if every person is a mountain of spiritual resources, but we don’t know how to mine them — one has huge reserves of iron in them, but we ask for silver; another has deep veins of copper, but we ask for nickel. We’re wasting each other’s gifts. We need to find the right ways to draw them out.

Steiner emphasizes this already in his first book, The Science of Knowing (he’s speaking about the place of the individual in society-at-large, but of course the same can be said about the place of the individual in any organization):

The point is for [a person’s] place within their people to be such that they can bring to full expression the strength of their individuality. This is possible only if the social organism is such that the individual is able to find the place where they can set to work. It must not be left to chance whether they find this place or not.8

He touches on this point again in another early writing:

We must create conditions so that those people who are especially suited for some sphere of life can place themselves within it. A profession will be best provided for when, out of its natural conditions, it’s able to bring into itself those people who are best fitted for it according to their nature. To create such conditions, however, there must be recognition and appreciation of the people who possess such fitness.9

So the task of bringing “to full expression” the strength of the individual, is a task that needs to be consciously facilitated today (“it must not be left to chance”), and it requires recognition and appreciation. As we’ll see, this isn’t just the task of the manager, we’re all responsible for it, and it’s far more difficult than we usually think. The case of the first Waldorf school is instructive in this regard.

Second example: a school

As a cultural institution, a school depends, above all else, upon the capacity and inspiration of individual teachers. There is no prescription for what to teach, no recipe to follow. When a teacher stands in front of their students and has to decide — on the spot — the next idea to bring, or the next experience to lead them through, in that moment education is always improvisation.

What teachers do can depend only to a slight extent on what the general standards of abstract, educational theory stimulate in them. It must rather be born anew, in each moment of their activity, out of their living understanding of the developing human being.10

Such inspiration and improvisation require freedom — they can’t be directed from outside — so teachers must be self-directed, “self-managing.” For this purpose Steiner recommended an organizational form that he described as “Republican” in nature. In it, there is no autocratic headmaster directing the teachers, nor the “tyranny of the majority” that we often find in democracies. Instead the school is guided by a “college of teachers.”

The college has two functions. On the one hand, it’s meant to be a true college, or “training academy,” for the teachers — the teachers are meant to continually study together, teach each other, and learn from each other’s experience. This is in line with today’s emphasis on continuing education and “learning organizations,” and Steiner describes it as the “soul and spirit” of the school:

No school is really alive where this is not the most important thing, this regular meeting of the teachers… This is the real purpose of the college meetings, to study human development, so that a real knowledge of the human being is continually flowing through the school.11

On the other hand, the college of teachers directs the school. In order to do this, the whole college must empower individual teachers to oversee certain administrative tasks (i.e., maintenance, hiring, marketing, etc.) for some period of time. It’s not that the teachers have to do these tasks — they’re just overseeing them — the idea being that the administration has to be aligned with, and flow out of, the inspiration of the teachers.

In these ways the school becomes teacher-led. The teachers are not just employees, they’re in charge. They’re responsible both for the “soul and spirit” of the school, as well as for the body — the external running of the school. Imagine how this alone could empower the teachers and affect their whole outlook.

So the teachers are given full freedom in the classroom; they’re called on to teach and give each other advice in the college; and they’re asked to oversee certain administrative tasks on behalf of the whole. In all of these places their individual strengths can find expression.

But even with such an organizational form — even in creating such conditions as these — it’s still difficult to empower each other because it requires us to recognize and appreciate each other. And the reality is, we’re often not so quick to see each other’s positive attributes; we often find it easier to criticize than to praise.

This means that a healthy organization — an organization where people work well together, and feel united and fulfilled — requires that people actively work to overcome their personal sympathies and antipathies, and simply try to cultivate interest in one another.

This wasn’t always the case at the first Waldorf school, and Steiner was quick to point out how disastrous it is when ill will poisons the water between people:

What one person does must flow over into the others, into the forces of the group. There must be joyful appreciation of individual achievements. There is [currently] not the goodwill… If I work and nothing happens, it is crippling. Negative criticism is only justified if accompanied by positive criticism. There is indifference with regard to positive achievements. People become stultified if nobody takes a scrap of notice of what they achieve.12

It’s easy to feel indifferent or hostile towards each other; it takes work to cultivate interest and trust. But without it, our work cannot flow together — cannot flow “into the forces of the group” — and instead our colleagues draw back into themselves; their forces, their strengths, are lamed.

So one can only expect that working in such an organization won’t be some utopian dream, but a difficult road — a road where new obstacles constantly arise between us, and where people fall back again and again on feeling hurt, annoyed, and critical of each other. But this is inevitable wherever people work together — our personalities grate on each other. It’s uncomfortable.

The only question is: what are we striving for in our work together, and how do we get there? If we’re looking for real health — for people to feel nourished by their work, and for a more profound spirit to enter the work between us — then Steiner’s insights are a kind of roadmap that can point the way across this rocky terrain.

The two basic mandates of a healthy organization

Based on Steiner’s Motto of the Social Ethic, as well as the specific indications he gave to organizations, we can say there are at least two basic mandates for how we should strive to work together within an organization:

We should strive to help all workers perceive the whole organization — the ins and outs of its everyday activities, as well as its larger purpose, the “meaning and value” of the work

We should strive to empower each worker to find their right place in the organization — the spot where they can best work out of their strengths at any given time

It’s important to emphasize that the above tasks are never complete; they’re an ongoing work. A person’s strengths are never stagnant — what they have to bring is constantly evolving as they develop and grow. And the organization is always changing, which is why the discussions and work between colleagues should be regular and ongoing. As Steiner says in his 1905-1906 essays, a worker needs to experience what a community or organization is as a “living, organic whole.” In those essays he goes on to say that:

He can only do this when the community is something other and quite different from a more or less indefinite totality of individual men… The whole communal body must have a spiritual mission, and each individual member of it must have the will to contribute towards the fulfilling of this mission. All the vague progressive ideas, the abstract ideals, of which people talk so much, cannot present such a mission... In every single member, down to the least, this Spirit of the Community must be alive.13

This “spiritual mission” is the star of the organization — what it’s aiming for, the “meaning and value” of its work. This can’t be some vague, abstract ideal, or ultimately it won’t have the force to truly motivate us. The organization has to be striving to realize and embody something in the world, in the context of society’s ongoing struggles. This is an essential part of how the worker develops a perception of the whole organization, by coming to understand how his work contributes to the whole of society (“the worker should be fully involved in the whole process, should be aware how his work in producing the goods relates him to the life of society…”)

And so we can see how the Social Motto (the “Motto of the Social Ethic”) contains within it the promise of real social health. It shows us what has to be done, difficult as it may be: to strive both for the freedom of the individual and the harmony of the whole, not by favoring one over the other, but by turning them towards one another. Instead of the clash of opposing interests, they become interested in each other.

It’s this concrete interest in the work itself and its effect upon the world, as well as the experience that one’s colleagues and community are truly interested in us and that there’s a place where we fit in — where we can bring our strengths and gifts — that can unify the workplace and nourish us as individuals. This is certainly not easy to accomplish. But nonetheless, it’s worth striving for.

For more on Steiner’s ideas around work, see “Your work is not a commodity. It's your reason for being here” and “Why organizations that do good are collapsing.”

Also, if you’re interested in working with these ideas more deeply, you can come to Wisconsin to participate in the work I’m doing with Robert Karp and Threefold Driftless, or invite us to your community or organization. In addition, I’ve developed a distance-learning course on Steiner’s social ideas as part of the courses offered by EduCareDo.

There are indeed a number of people who have worked in organizational development inspired by Steiner. Starting in the 1950s, Bernard Lievegoed is certainly the most notable, but there are also a number of contemporary practitioners including Otto Scharmer at MIT and the worldwide Association for Social Development. Nonetheless, very few have connected their work to Steiner’s ideas about social and societal transformation (what he called “social threefolding”). Lievegoed, for instance, was inspired instead by Steiner’s book An Outline of Esoteric Science to understand the developmental stages of organizations.

Steiner, Rudolf. “The Science of the Spiritual and the Social Question,” in Social Threefolding. Forest Row: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2018. p. 58.

This translation of the Social Motto by George and Mary Adams, is the best-known, but it has its short-comings. Namely, the original German doesn’t speak of the community finding its “reflection,” but being “formed” or “built up,” which is far more active. “Reflection” also suggests that there is a single, already-existing reality to the community, whereas “built up” suggests that this reality is being created. An alternative translation and short commentary on the Motto can be found here.

Besides teachers, Steiner worked with other professionals — doctors, farmers, priests, businessmen, etc. — and gave, at least some of them, indications for how to work together. I don’t know anyone who has collected these indications, but this would be helpful to understand how Steiner’s social thinking applies differently in different contexts. If you know of any such indications that Steiner gave to doctors, priests, or anyone else, please let me know.

Steiner, Rudolf. “Anthroposophy and the Social Question.” Spring Valley: Mercury Press, 1982.

Steiner, Rudolf. Towards Social Renewal, London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1999. pp. 67-68.

Hahn, Herbert. “How the Waldorf School Arose from the Threefold Social Movement” in Rudolf Steiner, Recollections by Some of his Pupils. Golden Blade, 1958. pp. 62-63.

Steiner, Rudolf. The Science of Knowing — Outline of an Epistemology Implicit in the Goethean World View. Spring Valley: Mercury Press, 1996. p. 108.

Steiner, Rudolf. “On the problem of the journalist and critic. On the occasion of the death of Emil Schiff on January 23, 1899.” GA 31. (Currently unpublished.)

Steiner, Rudolf. “The Pedagogical Basis of the Waldorf School,” from Francis Gladstone’s Republican Academies. Steiner Schools Fellowship Publications, 1997. p. 9.

Steiner, Rudolf. Kingdom of Childhood, Lecture 7. From Francis Gladstone’s Republican Academies. p. 2.

Steiner, Rudolf. Conferences with Teachers, Vol 3, from Francis Gladstone’s Republican Academies. pp. 18-19.

See footnote 5.

So grateful for this! It is profoundly timely!

Seth, This is really excellent! After reading it online, I had to print it out so I could go to work on it with underlining and highlighter.

I think the Mondragon Cooperatives from Spain manage to travel a considerable distance toward the ideal of worker involvement in the whole of production and in continuous growth of individual workers.