What has real value? Invisible art, NFTs, and the ongoing craze for crypto

The difference between imaginary values and the value of the imagination

In the last couple months, the art world has seen two seemingly similar events take place, both of which raise interesting questions about the nature of what we value.

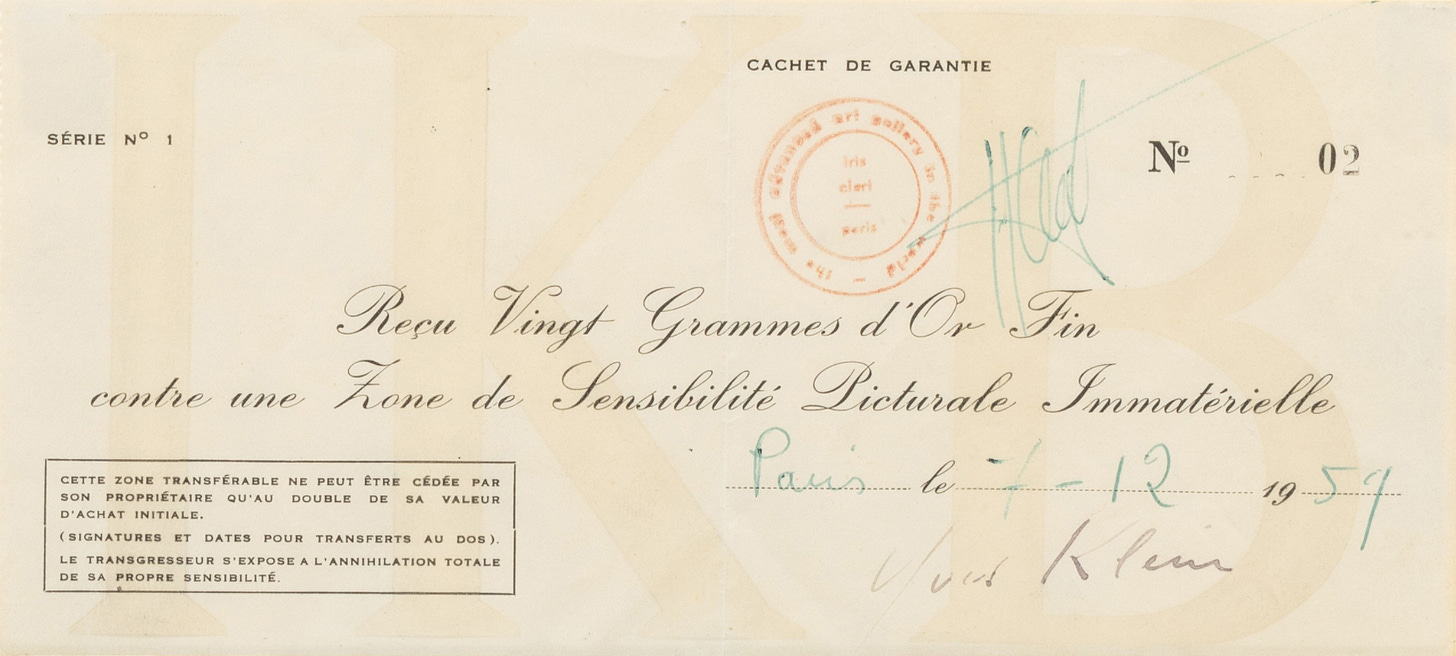

The first was the $1.2m sale of a receipt for a piece of invisible art. From 1959 until his death in 1962, the French artist Yves Klein sold 8 such receipts for what he called Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility. What are these zones? They’re often referred to as “empty spaces,” but Klein himself described them in various ways, one of which was as the fundamental essence of painting — as “invisible and intangible radiance.” And what exactly does that mean? From what I can tell, Klein is referring to the “ambiance” or inner experience that one can have in the presence of great works of art.

And so Klein did not merely sell these zones, but tried to bring people directly into that invisible presence. This was the true work of art. He did so by presenting the buyer with a choice:

“As Klein establishes in his ‘Ritual Rules,’ each buyer has two possibilities: If he pays the amount of gold agreed upon in exchange for a receipt, Klein keeps all of the gold, and the buyer does not really acquire the ‘authentic immaterial value’ of the work. The second possibility is to buy an immaterial zone for gold and then to burn the receipt. Through this act, a perfect, definitive immaterialization is achieved, as well as the absolute inclusion of the buyer in the immaterial.”1

So the buyer could make his purchase (the zones cost anywhere between 20-160 grams of gold), receive his receipt, and walk away. After all, the receipt was his and it was likely a very profitable memento — Who would want to burn it? Or he could take part in a ritual process where, in front of a number of witnesses, he would burn the receipt while, at the same time, Klein threw half of the gold into an ocean or river (the other half was to be used in future artworks).

The catch was: if the receipt wasn’t burned then there was no perfect immaterial state to be had — the art had to be enacted. In that case, the buyer didn’t get what they purchased, but just the receipt for it. It’s one of those receipts that sold last month for $1.2m.

The second event had to do with the auction of what has been called the “Mona Lisa of the digital world” — an NFT of Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s first ever tweet (see below). Don’t know what an NFT is? No worries. The NFT industry has been booming for the last two years, but here are the basics for the uninitiated.

NFT stands for “non-fungible token” and they, too, are a kind of immaterial artwork. For one thing, they exist purely in the realm of the digital. Their main selling point is that, in a realm where nothing is singular — where anyone can make a copy of anything and one copy is as good as the next — NFTs create a sort of “one-of-a-kind” version of an artwork (they’re “non-fungible,” meaning they’re not interchangeable, they’re unique). So the main thing they do is make an artwork exclusive. They introduce scarcity into the realm of digital art.

How they do this is through a somewhat loose relationship to the underlying artwork itself, which is the second reason we can call NFTs “immaterial.” When an NFT is sold, it’s not the image or song that’s purchased, it’s not even the copyright for the image or song, but instead a marker or unit of data (a “token”) that exists on a digital ledger called a blockchain. So anyone anywhere can still own a copy of the art, but the person who buys the NFT now owns a unique certificate of sorts — a certificate certifying they own… the certificate. (I know, it’s pretty confusing. Just think of it like buying a receipt for a piece of art instead of the art itself, which is why the auction house that sold the receipt for the Yves Klein Zone claimed it was the first ever NFT.)

The reason why the Jack Dorsey NFT made the news so spectacularly is because, out of nowhere, people started wondering if it was really worth anything. It was initially purchased a year ago for $2.9m and the original buyer was so confident of its value that, when he put it up for sale a few weeks ago, he raised the price tag to a hefty $48m. But then, a week later, he had the price tag quietly removed when the first week of bidding barely reached a few hundred dollars.

So what’s going on here? Are such artworks actually valuable, or are they simply scams? And what do we mean by “value” anyways? To answer such questions, let’s compare them to something that has no real value at all — cryptocurrencies.

But some will cry out “Of course crypto has value! My son-in-law has made a fortune on it!” And so he has. And so can anyone make a fortune on anything (or on nothing, as it turns out). Today’s crypto craze is basically the same as the tulip mania of the 1630s when Dutch people got so pants-on-fire excited about tulips that they drove up the price to the point where a single bulb cost more than a whole house. And, yet, when the tulip bubble burst it didn’t destroy the Dutch economy whereas the crypto bubble is beginning to engulf and endanger the whole global economy.

But let’s look a little more closely at crypto and see why it’s valueless — why it’s only an imaginary or pretend value. The main reason is because it’s not creating any real good that anyone can use; it’s not creating anything at all, and instead just consuming colossal amounts of energy (Bitcoin alone consumes more energy than Finland, a country of around 5.5m people).

But besides the fact that it’s an absolutely tragic waste of resources, it’s just gambling, pure and simple. Essentially it’s no different than a pyramid scheme: The lucky few (the “early adopters”) get in early and, when the music stops, walk away with everyone else’s cash. Everyone who joins at the end loses. So if you do decide to join, you have to pray it’s not yet the end.

But what does your prayer really amount to? You’re praying that still other people will join after you, and that you’ll get their money when they lose everything. I don’t mean to be harsh, but it’s a thief’s prayer. It’s not a prayer that’s fit for the ears of gods, nor even of children.

Cryptocurrency is not a currency but a speculative asset. People buy it in order to “flip” it, like shares in a company, or houses in a housing bubble, or tulips in a wild speculative flower frenzy. But with those other things there was at least the possibility of creating some value for society. There was the possibility of participating because you wanted to serve some greater good — because you wanted to lend money to a valued business, or aspired to fix up a home, or because you just really, really loved tulips.

But you can’t buy crypto for selfless reasons, it excludes the possibility. There is no greater good to be served through it: everyone’s in it only for themselves; it’s a war of all against all. Basically, you and your neighbor have pooled your money, and for what grand purpose? To start some new initiative? No — instead only to create the possibility for one of you to win it all and leave the other destitute. And so, in the final tally, the desires of a few will be indulged, while need, poverty, and suffering will result for the rest.

This can be tricky to understand, indoctrinated as we all are with the capitalist belief that self-interest magically benefits society, that greed is good. And this is why crypto is actually so useful for us today, because it lays bare the absolute bankruptcy of that idea. It strips it down to its most basic logic, which is this: If working only for one’s own profit is truly healthy, then why not drop the work entirely and pursue pure profit? Why produce anything to meet anyone else’s needs?

So what do we find when pure self-interest reigns? That nothing is produced. The more self-interest, the more we starve.

I’m definitely not saying that people who buy crypto are bad people. I have friends and family who buy it; really, it seems like just about everyone is buying it. My point is simply that everyone has bought into a scam, and actually not a very difficult one to spot.

Part of the problem is that we have such complete faith in authority. How could our business leaders and politicians2 all be wrong on crypto? How could they condone something that might crash the whole economy? Well, here’s a little story about that…

In the early 90s, Albania (down in Southeastern Europe) left its communist past and became a modern capitalist country. Within a few years, huge pyramid schemes — gussied up as “investment firms” — had sprung up everywhere, and two-thirds of the country’s entire population invested in them. People sold everything they had — their businesses, their homes, their cows — to invest in these schemes because they saw early adopters getting huge returns.

Everyone was doing it. Even the president and finance minister were doing it. At the same time, though, everyone also knew they were pyramid schemes… but if everyone was investing, how dangerous could they be? Could everyone be wrong? Were they really all suffering from some mass delusion? Unfortunately, they were.

So what happened? The only thing that could. In 1997 the schemes collapsed. The economy crashed. Everyone lost their money. There was rioting in the streets. Then the government fell, and the country descended into civil war.

So, coming back to where we started: how does art — and especially purely imagined works of art such as the Zones of Yves Klein — compare to the purely imaginary “values” created in crypto?

They are like night and day. One is a total spiritual nothingness, a destructive vacuum, and the other is a total spiritual potency, a fullness of possibility.

What I mean is that crypto is valueless because it doesn’t create anything of worth — it doesn’t feed anyone; instead, it steals their bread. But art can feed everyone. It can nourish all of us, and in the most health-giving ways.

Art feeds us by giving us the possibility to be moved inwardly, to be changed. We can leave a museum overwhelmed and exhausted with a few dozen pictures of ourselves standing in front of famous objects... or we can leave a different person, inwardly reconfigured by beauty, even if only in subtle ways.

We can zone out in front of the TV — lose ourselves, numb ourselves to the constant bombardment and quiet despair of life… or we can watch a film (or better yet a play!) where we wake up to ourselves, where some aspect of what it means to be human cries out in us and spurs us on to the task of making the world more beautiful and true.

Because, for those seeking it, art can be a doorway to the spirit. And whether or not you think he was successful, Yves Klein was seeking it. He knocked on that door with each one of his creations. He tried, as he could, to walk the paths of Zen Buddhism and Christian Rosicrucianism. He was struck by the words of the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who wrote “First there is nothing, then there is a deep nothing, then there is a blue depth,” and used that inspiration to create work after work of blue monochromes — paintings made up entirely of blue that, like the sky, are a last veil between humans and the void. He wanted to know the spirit that can be found in that void, in that so-called nothingness, and so he tried to leap into it, and to help us leap into it with our imaginations.

Of course this might just sound like new age claptrap to you. Who cares about “spiritual nourishment” when people all over the world don’t have enough food to eat. But the value of the imagination is not only for the imagination — it doesn’t only feed our souls and give our lives meaning (though really, that’s more than enough justification for it) it also feeds our stomachs. Or more accurately, it enables us to feed our stomachs.

This was an important observation of the 20th century social theorist Rudolf Steiner who was a great champion of culture, not only for cultural reasons, but for political and economic reasons as well. In his major work on economics, World Economy3, he observed that free cultural workers (those artists, educators, scientists, etc., who work freely out of their own inspiration) actually engender the conditions for creative work throughout society. They charge the atmosphere with a creative striving that leads to innovation, invention, and discovery more broadly. Here’s how Steiner put it:

“Free spirits have the peculiar property of loosening and liberating the spirituality, the ‘gumption’ of the others. They make their thinking more mobile, and these others are thus able to work into the material process more effectively.”

So art is by no means valueless. On the contrary, it’s one of the most valuable things in the world. But its value is immaterial. It’s not in the physical paint or the film or the soundwaves; it’s in the inner movement it creates. It’s in the beauty that stirs in us and the new ideas that alight. And not everyone experiences those things, because those experiences don’t force themselves on us. We have to participate. We have to be open.

Yves Klein saw this. He tried to point us away from matter to its true spiritual source. He urged us to trade in our material gold for the gold of the spirit, but we continue in the other direction. We continue to cling to matter — to do whatever we can to capture physical gold. We even lock up our art in high security storage facilities, never to be seen again, but instead to become items in a digital database, mere tokens to be traded back and forth by the superrich.

So, are the Yves Klein Zone and the Jack Dorsey NFT scams or not? There’s no objective way to tell. But we can ask a couple questions. One is, What are the artist’s intentions? When we ask this, we find that Klein was at least trying to move us inwardly, whereas NFT creators are very often just trying to make a buck by making art scarce. And we can also ask whether either work actually feeds anyone4 — Do they feed you? If so, they’re productive, they create some value. If not (and if they never really intended to), then they’re just a distraction.

What it comes down to is that we always have a choice: we can spend our lives gambling, or we can get down to the very real work of imagining, and striving to create, a more beautiful world. If you want to help in that task — and there’s a place in it for each of us — then I’d recommend letting go of crypto and the other imaginary values we’re all so obsessed with. I’d recommend burning the receipt.

Yves Klein, Berggruen Hollein & Pfeiffer, Hatje Kantz 2004 p. 221 (from the Wikipedia page Zone de Sensibilité Picturale Immatérielle).

And it’s not just the business leaders and politicians that are getting behind crypto, but perhaps most heart-breaking of all, Matt Damon. Last fall he starred in an epic commercial comparing crypto speculators to astronauts and explorers, with the rousing slogan “Fortune Favors the Brave.” But are crypto enthusiasts really widening humanity’s horizons in quite the same way… or are they more like those US bankers who “bravely” invented new financial instruments in order to repackage subprime mortgages? Are they more like the intrepid Neil Armstrong, or the plucky Bernie Madoff? In response to the commercial, the cartoon South Park did a pretty hilarious job of roasting Matt Damon.

This book has been variously translated as World Economy (Rudolf Steiner Press, 1990), Economics (New Economy Publications, 1993), and Rethinking Economics (SteinerBooks 2013).

When we ask whether either work “feeds” anyone inwardly, we can find some indications that the Yves Klein work has, in fact, changed people. When in 1962, Yves Klein transferred a Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility to the writer Michael Blankfort along the Seine river in Paris (the ritual ending with noonday church bells ringing all around the city), witnesses described the event as “extremely awe-inspiring” and Blankfort wrote of the event that he had had “no other experience in art equal to the depth of feeling of [the ritual transfer]. It evoked in me a shock of self-recognition and an explosion of awareness of time and space.”

Thank you very much for this, Seth! To me the difference between real value and false value is one of the most touching and interesting places in Steiner's threefold ideas... As well as the difference between spiritual value and pure commodity.

Have so much to say to this. First, you picked a horrible example of an NFT because the Jack Dorsey tweet isn’t trying to be “art.” It’s a piece of history (though don’t know it’s provenance, which to me would determine its value—did Jack mint it?). If you want to see real digital art that “nourishes” there are plenty of options. One of my favorite digital NFT artists is DeeKay Kwon. His piece “Life and Death” sold for $1m… check it out and tell me it doesn’t stir emotion: https://superrare.com/artwork-v2/life-and-death-33745

Check out this NFT museum for more examples of beautiful art: https://oncyber.io/6529om

I also disagree with you about crypto, but not going to write a big dissenting opinion here (save that for the next time we get together). I’ll grant you that there are a lot of scams in crypto, but argue that the underlying idea of cryptocurrency and the transparency and security that a blockchain provides is absolutely valid and will be a big part of our future. You mention somewhere that we believe in authority—it’s the opposite. Crypto is about pushing back on authority and a reaction to losing trust in government-backed currencies. I think you need to do more research on the possibilities that crypto creates. You’ve brought up the usual criticisms (energy usage, etc, which btw is being addressed by Ethereum’s move to proof-of-stake), but they reflect a basic understanding of the concept. There are speculators, sure, but there are also lots of people working in crypto for the public good and working in areas of regenerative finance and climate change (see: https://je.mirror.xyz/S-dpms92hw6aiacUHoL3f_iAnLVDvbEUOXw7wpy7JaU) or what the Optimism team (Optimism is a layer 2 protocol that settles on the Ethereum blockchain) is doing with its “Retroactive Public Goods Funding” (see: https://medium.com/ethereum-optimism/retroactive-public-goods-funding-33c9b7d00f0c). While crypto attracts scammers and speculators, it also opens up a world of possibilities for transforming the way we interact with each other, organize under a common cause (have you researched DAOs?), fund projects for public good, etc.

I look forward to discussing next time we spend some quality time together!