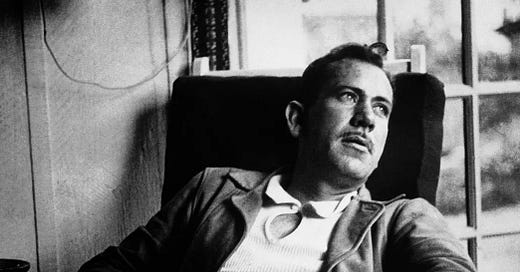

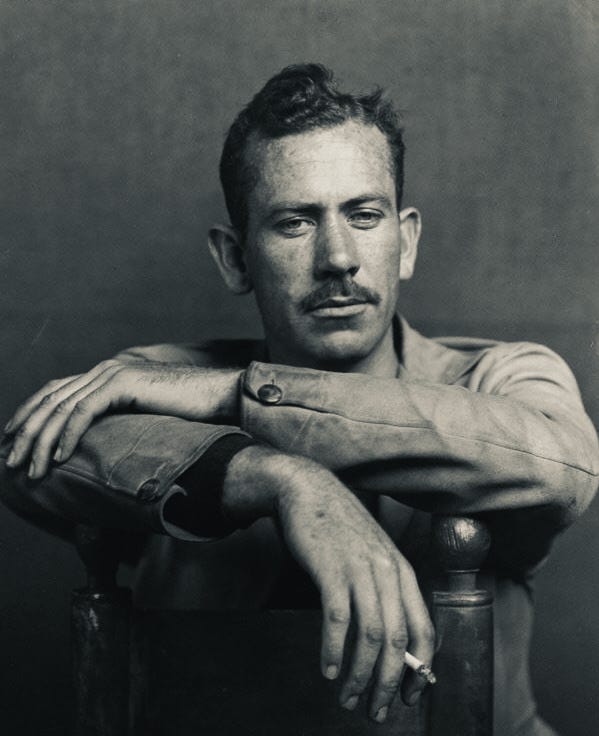

John Steinbeck, social mystic

His novel "In Dubious Battle" shows that he wasn't just one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, but one of its more profound spiritual and social thinkers as well.

“I could tell you some of the things I think; you might not like them. I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t like them.” — John Steinbeck

In reading John Steinbeck over the years, I’ve mostly seen him as a brilliant writer and a fierce social critic, one with deep compassion, humanity, and humor. But it would be hard not to notice his mystical leanings as well.

His worldview is so broad, so expansive, that at times it slips into the otherworldly. On the one hand, his characters are often plain and rough — there’s a muscular realism to his writing. But every once in a while his stories take an unexpected turn and we suddenly find ourselves face to face with the fantastic.

Like when the narrative shifts in the Grapes of Wrath, and we loiter with a turtle on its epic, perilous journey across a country road. Or in Cannery Row when we hear about a boy named Andy who taunted an old “Chinaman” until “the old man stopped and turned… the deep-brown eyes looked at Andy… the eyes spread out until there was no Chinaman. And then it was one eye — one huge brown eye as big as a church door. Andy looked through the shiny transparent brown door and through it he saw a lonely countryside, flat for miles but ending against a row of fantastic mountains shaped like cows’ and dogs’ heads and tents and mushrooms. There was low, coarse grass on the plain and here and there a little mound. And a small animal like a woodchuck sat on each mound. And the loneliness — the desolate cold loneliness of the landscape made Andy whimper because there wasn’t anybody at all in the world and he was left…”

But such scenes can always be chalked up as strange interludes in an otherwise “normal” story, inconsequential flights of fancy that the reader easily forgets. And maybe that’s all Steinbeck’s mysticism amounts to — a bit of playful fun, a little eccentric humor that shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

At least that’s what I thought until I recently read Steinbeck’s 1936 novel In Dubious Battle. It has been hailed as “the best strike novel ever written” and it is indeed a wonder to behold.

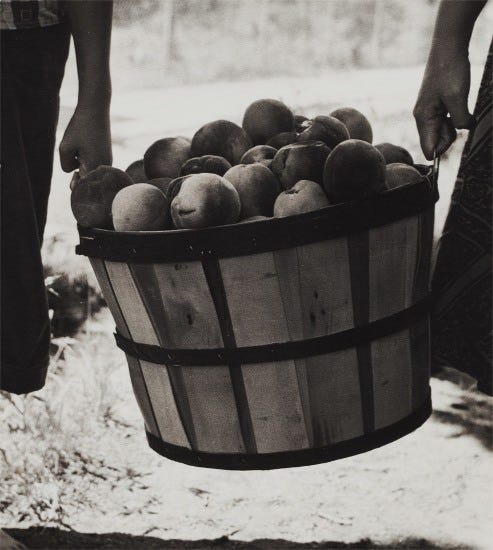

On the surface, it too is gritty and realistic — a story of two communist organizers working with down-and-out migrant farmworkers in the apple orchards of California. The book is full of people rubbed raw by life, stretched to the limit. We see them scraping by — beaten, hungry, exhausted, and angry. We see them trudging through the mud by morning, and huddled around fires in their makeshift shanty towns by night.

It is perhaps the most visceral, the most earthy and physical of Steinbeck’s books. And perhaps for this reason it’s also the most metaphysical. For it can be in such challenging conditions — conditions of chaos and confusion — that the spiritual is especially able to break through.

In Dubious Battle is an exploration of how the spirit interacts with the social — how the spirit works into groups of people. It’s because of this that I’ve called Steinbeck a “social mystic.”

The whole book is basically a study in group-think and group-beingness.1 Because something happens when we come together. We change. We act differently. The borders of our individuality can loosen and dissolve.

And a mass of men isn’t just the sum of its parts — it’s not this man, and this man, and this man. It becomes something more, something other. It becomes its own being, it’s own superorganism. The characters in the novel refer to the group as an “animal.”

And when the group nature is unconscious, dark things can take place. Individuals can be moved by invisible forces larger than themselves. They can become possessed, and the group can become a violent mob.2 But we all live and work in groups, and we obviously know that’s not all they are. So there’s a larger reality that needs to be explored and understood. The nature of the group doesn’t have to remain unconscious. It can be brought to consciousness.

In the book there’s a doctor that’s trying to do this. His name is Doc Burton and he works in the camp where the men are striking. He has worked in a number of such camps over the years, but he’s not a communist. He simply wants to understand the nature of such groups and also heal those who are hurt.

In one of the scenes he’s questioned by one of the two communist organizers, whose name is Mac:

Mac spoke softly, for the night seemed to be listening. “You’re a mystery to me, too, Doc.”

“Me? A mystery?”

“Yes, you. You’re not a Party man, but you work with us all the time; you never get anything for it. I don’t know whether you believe in what we’re doing or not, you never say, you just work. I’ve been out with you before, and I’m not sure you believe in the cause at all.”

Dr. Burton laughed softly. “It would be hard to say. I could tell you some of the things I think; you might not like them. I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t like them.”

“Well, let’s hear them, anyway.”

“Well, you say I don’t believe in the cause. That’s like not believing in the moon. There’ve been communes before, and there will be again. But you people have an idea that if you can establish the thing, the job’ll be done. Nothing stops, Mac. If you were able to put an idea into effect tomorrow, it would start changing right away. Establish a commune, and the same gradual flux will continue.”

“Then you don’t think the cause is good?”

Burton sighed. “You see? We’re going to pile up on that old rock again. That’s why I don’t like to talk very often. Listen to me, Mac. My senses aren’t above reproach, but they’re all I have. I want to see the whole picture — as nearly as I can. I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and limit my vision. If I used the term ‘good’ on a thing I’d lose my license to inspect it, because there might be bad in it. Don’t you see? I want to be able to look at the whole thing.”

. . . “I want to see,” Burton said. “When you cut your finger, and streptococci get in the wound, there’s a swelling and a soreness. That swelling is the fight your body puts up, the pain is the battle. You can’t tell which one is going to win, but the wound is the first battleground. If the cells lose the first fight the streptococci invade, and the fight goes on up the arm. Mac, these little strikes are like the infection. Something has got into the men; a little fever had started and the lymphatic glands are shooting in reinforcements. I want to see, so I go to the seat of the wound.”

“You figure the strike is a wound?”

“Yes. Group-men are always getting some kind of infection. This seems to be a bad one. I want to see, Mac. I want to watch these group-men, for they seem to me to be a new individual, not at all like single men. A man in a group isn’t himself at all; he’s a cell in an organism that isn’t like him any more than the cells in your body are like you. I want to watch the group, and see what it’s like. People have said, ‘mobs are crazy, you can’t tell what they’ll do.’ Why don’t people look at mobs not as men, but as mobs? A mob nearly always seems to act reasonably, for a mob.”

“Well, what’s this got to do with the cause?”

“It might be like this, Mac: When group-man wants to move, he makes a standard. ‘God wills that we re-capture the Holy Land’; or he says, ‘We fight to make the world safe for democracy’; or he says, ‘we will wipe out social injustice with communism.’ But the group doesn’t care about the Holy Land, or Democracy, or Communism. Maybe the group simply wants to move, to fight, and uses these words simply to reassure the brains of individual men. I say it might be like that, Mac.”

. . . “This isn’t practical,” Mac said disgustedly. “What’s all this kind of talk got do with hungry men, with layoffs and unemployment?”

. . . “I simply want to see as much as I can, Mac, with the means I have.”

Mac stood up and brushed the seat of his pants. “If you see too darn much, you don’t get anything done.”

Burton stood up too, chuckling softly. “Maybe some day — oh, let it go. I shouldn’t have talked so much. But it does clarify a thought to get it spoken, even if no one listens.”

. . . Burton laughed apologetically. “I don’t know why I go on talking, then. You practical men always lead practical men with stomachs. And something always gets out of hand. Your men get out of hand, they don’t follow the rules of common sense, and you practical men either deny that it is so, or refuse to think about it. And when someone wonders what it is that makes a man with a stomach something more than your rule allows, why you howl, ‘Dreamer, mystic, metaphysician.’ I don’t know why I talk about it to a practical man. In all history there are no men who have come to such wild-eyed confusion and bewilderment as practical men leading men with stomachs.”

“We’ve a job to do,” Mac insisted. “We’ve got no time to mess around with high-falutin’ ideas.”

“Yes, and so you start your work not knowing your medium. And your ignorance trips you up every time.”

Here’s a character who wants to understand, who wants to see things for what they really are, who wants to see things in their wholeness.

Why? Because it’s their actual reality. Because this is the actual medium of social life — the intricate dance of group dynamics. But “practical” people have no use for it, they simply want things to go their way so they blindly push in that direction (and really, almost all of us do this). But it won’t work in the long run. Our actions have to accord with reality, otherwise they’ll come back to bite us.

This might all sound a bit philosophical, but the beautiful thing about In Dubious Battle is that we get to watch these group dynamics unfold in real time. We get to see them in action.

We watch the mob as it boils and cools. We see how the leaders rile up the men when they need them hot. We see how fickle, how sensitive, the mob’s mentality is. And we see how individuals get swept up in the mob and lose themselves.

The most extraordinary example of this ‘losing oneself’ has to do with the other communist organizer, Jim Nolan. Jim is the young protagonist of the novel. He’s totally green, totally new to organizing. It’s his first assignment and he’s under Mac’s tutelage. But although he’s totally inexperienced, he’s also well-read. His approach is through the intellect. He knows the ideas and strategies of communism, but he knows them all abstractly.

Now, after a week of non-stop action — after train-hopping, and delivering a baby, and going hungry, and slaughtering a cow, and fighting with “scabs” (the replacement workers brought in from the city), and being shot in the arm — he’s naturally been pushed to the brink. Which makes him a perfect candidate for losing himself.

But what does this loss of self look like? We don’t often see it, perhaps because the faceless mob usually obscures it, and perhaps because we never really look. But we get to witness Jim’s transformation. We get to see him lose himself. And we see something else enter into him. We see him possessed.

In this particular scene, the leaders have just done something dark. (I should mention that the official leader of the group is a big guy named London — he’s one of the workers and was elected to lead the strike — but Mac and Jim are consulting London along the way.) In this scene the guards around the camp have captured a young fellow, a high schooler, who was sneaking around with a gun hoping to scare the strikers. Mac feels he has to make an example of him in order to deter other locals from doing the same thing, so he beats the kid up pretty good. It’s a cold, calculated move, and in order to do it, one has to split one’s soul — one has to separate off that part of oneself that would naturally be compassionate and humane. This is the final straw for Jim:

The guards took the boy under the arms and helped him out of the tent. Mac said, “London, maybe you better put out patrols to see if there’s any more kiddies with cannons.”

“I’ll do it,” said London. He had kept his eyes on Mac the whole time, watching him with horror. “Jesus, you’re a cruel bastard, Mac. I can unda’stand a guy gettin’ mad an’ doin’ it, but you wasn’t mad.”

“I know,” Mac said wearily. “That’s the hardest part.” He stood still, smiling his cold smile, until London went out of the tent; and then he walked to the mattress and sat down and clutched his knees. All over his body the muscles shuddered. His face was pale and grey. Jim put his good hand over and took him by the wrist. Mac said wearily, “I couldn’t of done it if you weren’t here, Jim. Oh, Jesus, you’re hard-boiled. You just looked. You didn’t give a damn.”

Jim tightened his grip on Mac’s wrist. “Don’t worry about it,” he said quietly. “It wasn’t a scared kid, it was a danger to the cause. It had to be done, and you did it right. No hate, no feeling, just a job. Don’t worry.”

. . . Mac looked at him with something of fear in his eyes. “You’re getting beyond me, Jim. I’m getting scared of you. I’ve seen men like you before. I’m scared of ‘em. Jesus, Jim, I can see you changing every day. I know you’re right. Cold thought to fight madness, I know all that. God Almighty, Jim, it’s not human. I’m scared of you.”

Jim said softly, “I wanted you to use me. You wouldn’t because you got to like me too well.” He stood up and walked to a box and sat down on it. “That was wrong. Then I got hurt. And sitting here waiting, I got to know my power. I’m stronger than you, Mac. I’m stronger than anything in the world, because I’m going in a straight line. You and all the rest have to think of women and tobacco and liquor and keeping warm and fed.” His eyes were as cold as wet river stones. “I wanted to be used. Now I’ll use you, Mac. I’ll use myself and you. I tell you, I feel there’s strength in me.”

“You’re nuts,” said Mac. “How’s your arm feel? Any swelling? Maybe the poison got into your system.”

“Don’t think it, Mac,” Jim said quietly. “I’m not crazy. This is real. It has been growing and growing. Now it’s all here. Go out and tell London I want to see him. Tell him to come in here. I’ll try not to make him mad, but he’s got to take orders.”

Mac said, “Jim, maybe you’re not crazy. I don’t know. But you’ve got to remember London is the chairman of this strike, elected. He’s bossed men all his life. You start telling him what to do, and he’ll throw you to the lions.” He looked uneasily at Jim.

“Better go and tell him,” said Jim.

“Now listen-’

“Mac, you want to obey. You better do it.”

Then there’s a whole scene where Jim talks with London and tells him what to do. As you can imagine, London is baffled — What the hell has come into this young upstart? And London doesn’t like Jim’s directions either. Instead of the strike being a more-or-less disorganized expression of collective action, Jim wants London to take control and use rifles to force the men to do his bidding (to which London responds, “The whole thing sounds kind of Bolshevik”3). But London can also sense the authority in Jim, the power working in him, so he begrudgingly does what he’s told. Then the scene continues:

After [London] had gone out, Mac still stood beside the box where Jim sat.

“How’s your arm feel, Jim?” he asked.

“I can’t feel it at all. Must be about well.”

“I don’t know what’s happened to you,” Mac went on. “I could feel it happen.”

Jim said, “It’s something that grows out of a fight like this. Suddenly you feel the great forces at work that create little troubles like this strike of ours. And the sight of those forces does something to you, picks you up and makes you act. I guess that’s where authority comes from.” He raised his eyes.

Mac cried, “What makes your eyes jump like that?”

“A little dizzy,” Jim said, and he fainted and fell off the box.

. . . Mac unbuttoned Jim’s shirt. He brought a bucket of water that stood in a corner of the tent, and splashed water on Jim’s head and throat. Jim opened his eyes and looked up into Mac’s face.

“I’m dizzy,” he said plaintively. “I wish Doc would come back and give me something. Do you think he’ll come back, Mac?”

“I don’t know. How do you feel now?”

“Just dizzy. I guess I’ve shot my wad until I rest.”

“Sure. You ought to go to sleep. I’m going out and try to rustle some of the soup that meat was cooked in. That’ll be good for you. You just lie still until I bring it.”

When he was gone, Jim looked, frowning, at the top of the tent. He said aloud, “I wonder if it passed off. I don’t think it did, but maybe.” And then his eyes closed, and he went to sleep.

So we can clearly see that Jim is unwell, past the point of even knowing it himself. And when he is most weak, most exhausted and vulnerable, something else “picks [him] up and makes [him] act.” And when he subsequently collapses, it disappears. Here’s how he relates to it the next day when he wakes up:

“Mac, did I make a horse’s ass of myself last night?”

“Hell, no, Jim. You made it stick. You had us eating out of your hand.”

“It just came over me. I never felt like that before.”

“How do you feel this morning?”

“Fine, but not like that. I could of lifted a cow last night.”

I don’t want to reduce the book, or Steinbeck’s ideas around ‘group-man,’ to these two scenes. A lot happens in this story and these scenes are simply symptomatic of the whole. It’s a fascinating read.

But I do want to point to Steinbeck’s larger social impulse and why it’s so important. Like Doc, Steinbeck wants to see. He thinks it’s important to look at the world, to really look at things for what they are. To take an interest in the world and other people. If we don’t, then we’re in danger of losing ourselves, losing our individuality, losing our humanity.

Jim Nolan is a good guy. He’s a young guy with ideals. He wants to make the world a better place. But like most of us, he’s not actually that interested in looking closely at the world, he just wants to impose his own ideas upon it. Steinbeck makes this clear towards the end of the book when Jim says to Mac:

“Mac, do you s’pose we could get a leave of absence some time and go where nobody knows us, and just sit down in an orchard?”

“‘Bout two hours of it, and you’d be raring to go again.”

“I never had time to look at things, Mac, never. I never looked how leaves come out. I never looked at the way things happen. This morning there was a whole line of ants on the floor of the tent. I couldn’t watch them. I was thinking about something else. Some time I’d like to sit all day and look at bugs, and never think of anything else.”

“They’d drive you nuts,” said Mac. “Men are bad enough, but bugs’d drive you nuts.”

“Well, just once in a while you get that feeling — I never look at anything. I never take time to see anything. It’s going to be over, and I won’t know — even how an apple grows.”

Compare Jim’s “I never look at anything” to Doc Burton’s “I want to be able to look at the whole thing… I want to see.” We know Steinbeck himself was an incredibly keen observer of life — his books are a testament to it. He can describe how an apple grows and how a turtle crosses a road. He has looked. He has seen.4

And so of course, he’s also aware of his own shortcomings. When he has a character in his book The Winter of Our Discontent say “I wonder how many people I’ve looked at in my life and never seen,” you can sense his own self-criticism. How much of life, and how many people, do we pass by unawares? How little do we see one another for who we truly are?

And Steinbeck also knew what it’s like to be unseen by others. He was not yet a popular writer when he published In Dubious Battle, and he had no expectation of it becoming the bestseller that it did. He thought the message would be too philosophical for people. And it was. The critics often hated his message (one went so far as to say that “Doc Burton’s psychological and philosophical theories nearly destroy the novel”). But still, the surface action of In Dubious Battle is so great that it won Steinbeck a huge audience.

But what is it to have an audience that loves the superficial aspects of your work and largely ignores your deeper message? Even Warren French, a biographer of Steinbeck and the first president of the John Steinbeck Society, totally misunderstood the nature of Jim Nolan’s possession.

In the introduction to the 1992 Penguin edition of the book, French states that In Dubious Battle is not a “metaphysical exploration of an individual’s relationship to a group,” but a classic coming-of-age story. And how does he characterize the arc of Jim Nolan’s coming-of-age?

This process of maturing usually takes years, but Jim Nolan is on a crash course… he has developed self-confidence and discovered the latent cunning that enables him to make a bid to take command of a deteriorating situation. He has made remarkable progress, proving himself an apt and resourceful student who quickly develops leadership abilities.

So instead of a young man losing his soul to a cold and violent spirit (largely because of his inexperience and abstract intellectualism), French sees a “self-confident… and resourceful student [with] leadership abilities.” And this was the first president of the John Steinbeck Society. To read his introduction after reading the book is like tracing a map of misunderstanding.5

Imagine how lonely Steinbeck must have been if this was how his biggest fans understood his work. I assume such a reception could only discourage him from speaking so explicitly about the spirit again.

I do know one other place where Steinbeck spoke about the spirit as directly — in his short description of Joan of Arc. The history of Joan of Arc is a testament to just how forcefully the spirit can work down into the material. It lays bare the true nature of inspiration — how spiritual beings are working with us all the time. Her story is the most dramatic imaginable, but also the most factual, the most well-documented, and so it is perhaps the most irrefutable outer evidence of the spirit’s working that exists.

In this essay, Steinbeck gives a concise overview of the impossibility — but nonetheless, actuality — of Joan’s deeds, and then leaves it at that, only softening it a little at the end so his readers won’t be so confronted by the facts. And this is also the case with In Dubious Battle. He brings the spirit as he’s able, but softens it. He gives his readers a good story and doesn’t confront them too directly. He lets them take what they want, even if it’s not the best that he has to give.

Maybe this is because it’s all that people would take and he so desperately wanted to write — he needed readers to buy his books. Or maybe it’s because he respected his readers too much to take away their freedom, to force them to recognize the spirit.

I think it’s probably a bit of both, and probably something else as well. I think Steinbeck simply had to write for his own development, for his own coming-of-age, regardless of what others did or didn’t understand of it. Because “it does clarify a thought to get it spoken, even if no one listens.”

Yes, writers have to eat, but paywalls just punish low-income people, and why shouldn’t they have access to the writing and ideas they want?

Steinbeck had a term for group-beingness — what he called the “phalanx” (it was originally a military term for a group of tightly packed infantrymen who work together as a single unit.) One can trace his ideas about the phalanx in many of his books, though I don’t know of any that are as explicit as In Dubious Battle. He also wrote an article about it entitled “Argument of Phalanx,” but it’s currently unpublished and one can only find quotes from it online.

Steinbeck describes the emotional exultation, and subsequent emptiness, of belonging to a lynching mob in his short story “The Vigilante” in The Long Valley.

By connecting Jim’s proposals to Bolshevism, Steinbeck points to the slippery slope from collective action to government-sponsored terrorism. But really it’s the danger inherent in working towards any higher cause where ‘anything goes’ — where the ‘ends justify the means.’ It also illustrates the fact that Bolshevism was imbued with a specific spirit, a being connected to the abstract intellect, cold and violent.

I’d say that Steinbeck, like many great novelists, quite naturally trained himself as a phenomenologist — he took time to really look at things and let their individual expression inform him. We can see this in his writing, but also in his interests. During his early life, he was close friends with the marine biologist Ed Rickets (who inspired the character “Doc” in Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday, and who died from an accident in the prime of his life). Steinbeck and Rickets went on scientific excursions together, one of which became the material for Steinbeck’s book The Log from the Sea of Cortez. Rickets must have been quite an inspiring person, as he was also friend and muse to Joseph Campbell and Rachel Carson.

In Dubious Battle is full of profound insights, many of which will likely be familiar to students of social threefolding. Unfortunately, French misunderstands almost all of them. Two that Steinbeck expressed through Doc Burton in the aforementioned quote are:

His insight into the constant evolution of social reality (“you people have an idea that if you can establish the thing, the job’ll be done. Nothing stops, Mac…”). In the introduction, French describes this insight as “conventional” today because of the fall of the Soviet Union, as if Steinbeck was merely pointing out the inadequacy of communist social reforms. But Steinbeck is describing the shortsightedness of all social reforms (and reformers), because of our unconscious belief that our reform is a kind ‘cure all’ or end solution, and not just another step on the path, to be followed by future reforms.

His insight into the nature of social objectivity (“I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and limit my vision…” ). After completing the book, Steinbeck wrote to a friend that the book was not a work of advocacy, but that he had striven only to be a “recording consciousness” of the labor struggle. French believed that Steinbeck failed in this respect, because French thinks that such objectivity in social science would entail giving equal voice to all parties (adopting what some philosophers have called a ‘view from nowhere’), instead of Steinbeck’s true intention — to present what is taking place unadorned, without personal judgement, without shrinking from its brutality or hiding the complexities of the people involved. In Dubious Battle is not a tidy narrative that tells you who is good and who is evil. Like all of life, the story is complicated, unclear, a bit “dubious.” And so the reader is left to make such judgements for themselves.

Gourgeous and beautiful. East of Eden is among the most transformative anchors in the development of my psyche. Thank you for bringing attention to correlations these many years later.

So instead of a young man losing his soul to a cold and violent spirit (largely because of his inexperience and abstract intellectualism), French sees a “self-confident… and resourceful student [with] leadership abilities.” And this was the first president of the John Steinbeck Society. To read his introduction after reading the book is like tracing a map of misunderstanding.5

Horrific.

Thank you for this piece - it's a beautiful bit of writing, perfectly structured, and lovingly paced. x