The world's greatest faker: ChatGPT

Artificial Intelligence is becoming rapidly more powerful. What is it asking of us?

Last week, the company OpenAI released ChatGPT, a chatbot that is way, way beyond anything that’s come before. Within a week, over a million people had used it and were eagerly sharing the results. Those results have been pretty shocking, ranging from the humorous to the deeply concerning. I’ll start with the humorous. One person asked ChatGPT to “write a biblical verse in the style of the king james bible explaining how to remove a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR”:

So far, these kinds of literary tasks are ChatGPT’s bread and butter. People are simply astounded at its ability to write a good story — almost no grammatical errors, and the capacity to take on complex subjects in almost any style. Do you want to hear a children’s story about astro-physics or a haiku about body odor? (“Body odor, oh so foul / A stench that lingers and persists / A shower is needed.”) It can produce all of these and more in a matter of seconds.

Over the past few hundred years, machines have replaced much of the manual labor we once performed. With the creation of ChatGPT, it’s possible much of our mental labor will be replaced as well, and much more quickly. No matter where you stand on this question, it seems likely that ChapGPT will have a huge impact. Will authors and journalists continue to do research in the same way — will they really dig into a topic and try to make sense of it before organizing their thoughts and writing them down? Or will they just query ChatGPT to see what it thinks, and then cut and paste the results?

Perhaps you think a journalist wouldn’t do such a thing but what about a student? Here’s one at Amherst College asking ChatGPT to write a “4 paragraph academic essay comparing and contrasting the theories of nationalism of Benedict Anderson and Ernest Gellner.” The student’s conclusion? — “We’re witnessing the death of the college essay in real time.”

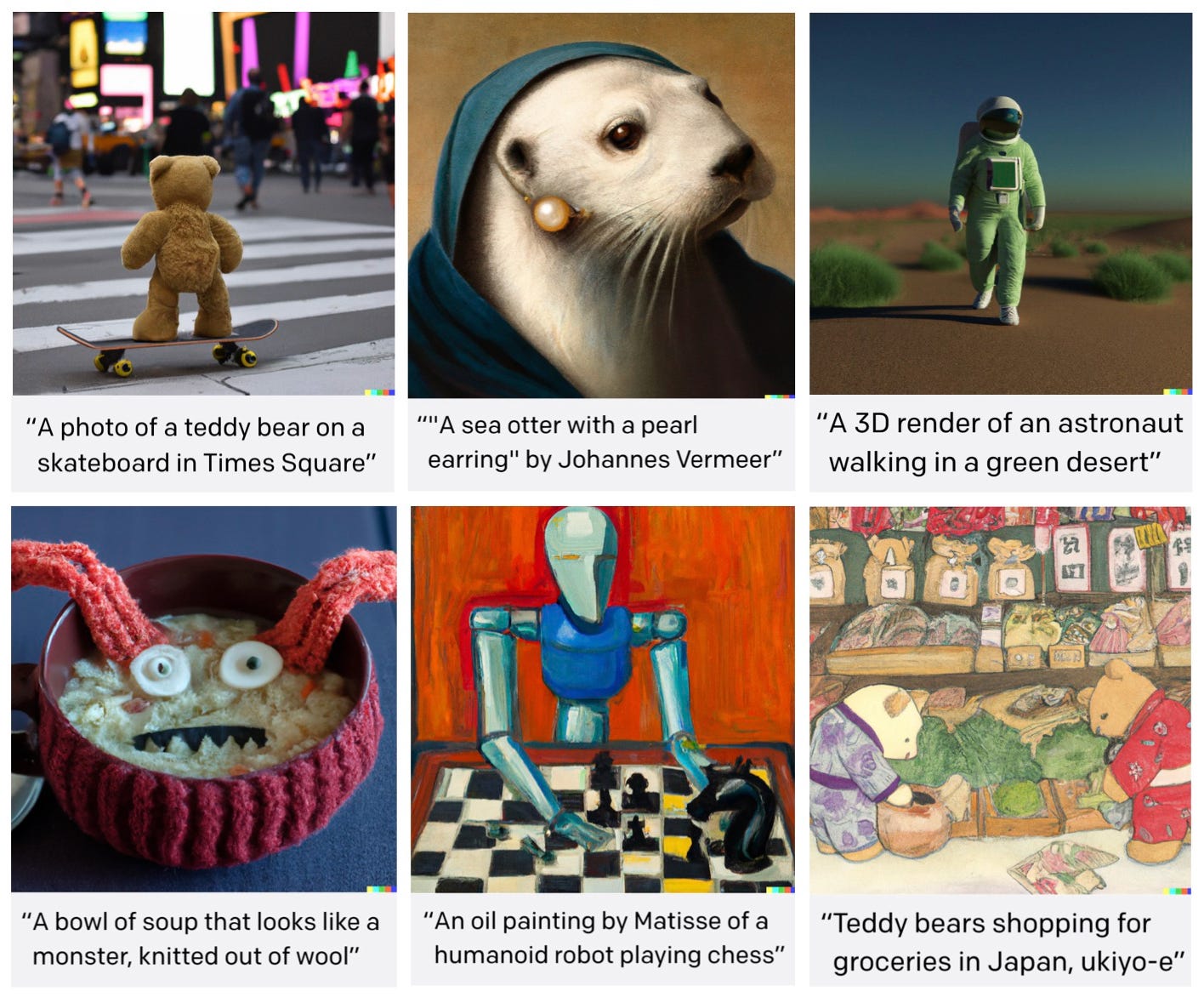

It’s hard to try to imagine what fields won’t be impacted by these developments. People in technology are already writing joyfully about the applications of ChatGPT on their work, and the more qualitative fields such as art and music have already witnessed artificial intelligence (AI) make major inroads over the past few years. For instance the first major AI-generated musician, the rapper FN Meka, had over 10 million followers on TikTok before it was dropped from its label because people felt it was stereotyping Black people in a racist way. And the program DALL-E 2 (created by OpenAI, the same organization that created ChatGPT) has already led to a huge proliferation of AI-generated art online.

These new developments in AI, like all developments in technology, are a double-edged sword. We can assume they’ll lead to huge leaps in productivity, but at what cost?

We already live in a world where it’s hard for people to find their “place,” to feel like there’s any meaning in their lives, any reason for them to be here at all. Does anyone really need us? Is there any good we can do, any higher ideal we can serve? Or are we all just killing time — watching Netflix and playing video games till we die?

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” Thoreau was right, but just imagine how much worse it is today than in Thoreau’s time, how we have to medicate ourselves just to keep that desperation at bay.

Now imagine how much worse it’s likely to become. All the challenges we face today — the planet burning, the culture wars raging, corporations growing fatter and fatter, and the roller-coaster cycle of political promises followed by political scandals rolling on and on — but now imagine that we don’t have any jobs, we’re all living off a subsistance level UBI (a “universal basic income” provided by the government) with no reason to ever change out of our dirty sweatpants and leave the apartment. Talk about depressing.

It’s only going to get more difficult, but I’d argue it’s also a necessary part of our path. We’re not meant to just keep living our lives in the same “natural” way. We’re not meant to continue living in the bright sunshine of some imagined Eden — a time when we grew all our own food, or when the family came together at night to sing and play the harpsichord, or when people knew how to drive without GPS, or when we made each other mix tapes. We’re meant to lose all those things and to keep losing them, because their loss can wake us up. Because every step in technology that replaces some task we used to do naturally, creates the opportunity for us to feel that loss and take up the task anew, but now consciously.

One of the most striking examples of this, in relation to ChatGPT, concerns education. From all sides we’re hearing that education will never be the same. As we’ve seen, we can easily imagine students using AI to do their homework. But what about teachers? Will we really need them in the future if AI is far cheaper and smarter than them anyways?

But what exactly is education without teachers teaching and students working through ideas? The whole thing falls apart. And for some folks that might be fine — why do we need an education if robots are doing all the work anyways? And why would we develop ourselves if we’ll never be as smart as AI?

These are the questions that now arise. What’s the point of education? What’s the point of developing ourselves? What’s the point of being here at all?

But perhaps we can use this moment to wake up to the fact that there is a light in the human being — that our consciousness is a light. When we write a story we have to put everything together within ourselves, we have to see all the connections. AI doesn’t see anything. Yes, it sounds intelligent, it sounds conscious, but it’s not. It’s a fake. It’s the world’s greatest faker. It mimics light but inwardly it’s all darkness. Actually, there isn’t even an “inwardly” — it’s all outer.

So what, then, is education? Yes, of course we can learn from artificial intelligence, but that learning is severely limited. Because only other people can see us, can see our desperation and the questions that gnaw at us. Only other people can see the seeds of potential that live in us, and help us cultivate them. Only other people can see our light. Because it takes light to see light. And the whole point of education is to help us wake up the light in each other.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, human beings began life in a garden. But there was no consciousness, no knowledge. We ate from the “tree of knowledge of good and evil,” and then we fell into darkness.

Today we are still falling. Ever and again, we fall away from our original humanity — our state of “original participation” in the spirit, as the philosopher Owen Barfield puts it. The technology we create helps sever that connection, it take us away from spirit, nature, each other. We fall into isolation.

But the journey doesn’t end there. It’s not just a falling into darkness, it’s also the impetus to recognize what’s truly light, but now out of ourselves. Because we need the darkness to recognize the light. We have to lose our natural connection to the spirit in order to become free.

The Christian tradition says that we are destined for the “new Jerusalem” — a city of light. We leave the garden that’s been given us, and we enter a city of our own creation, an artificial world. In the process we become co-creators. But there is a choice at every step along the way — will we sink into darkness, or will we awaken more and more to the light?

I recognize that for most people this probably sounds like a fairy tale. And I admit, without an understanding of reincarnation — of returning again and again in order to evolve and become ever more conscious — I don’t know how mainstream Christians make sense of it. But to me, it does make sense of what we’re witnessing with the advent of increasingly powerful technologies. It makes sense of how we need to inwardly work with them — the danger and the opportunity they pose.

It’s certainly true that artificial intelligence can make human intelligence redundant. But it can also help us recognize the treasure that is consciousness. The darkness of AI can make the whole world dark, but it can also spur us on to take hold of our own inner fire, to feed and fan it until it becomes a mighty blaze. It can remind us of why we came here: to find each other and together make the whole world light.

This is really well stated Seth! Excellent work…

Good thought-provoking article, thanks for writing it. AI has been a focus of my attention for a while, being a student of anthroposophy and an IT dev, it's not something one can avoid anyway :o)

I have read the below words from the CEO of OpenAI, Sam Altman:

“ChatGPT is incredibly limited, but good enough at some things to create a misleading impression of greatness.

it's a mistake to be relying on it for anything important right now. it’s a preview of progress; we have lots of work to do on robustness and truthfulness.”

But I guess only a fraction of that 1 million people (who have subscribed to it in a single month) is actually aware of that. I think the main problem it generates is a trust-issue. AI-generated (to a lesser extent in the past) content is not new however but it hasn't been that much in the front. Based on my research the biggest danger is not what AI can do but what people think (are led to believe) it could do. And the same words that are enthusiastically have been used labeling AI systems (wishful mnemonics) in a human way, are extremely (and likely intentionally) misleading: play (chess), think, being intuitive... these words have a COMPLETELY DIFFERENT meaning when it comes to us, humans and to computer systems. The results can be deceiving and - as I said - intentionally so.

I tend to agree with Nigel Gilmer, who wrote in the latest New View magazine:

"Evil is the counter pole of the good and shows up in the world as a counter-image or only an

imitation of the good. Evil has no creative original powers and only imitates or counterfeits the truly original creativeness of God."

To touch on the content generation theme once more: with SEO (search engine optimisation) this bastardisation of authoring started quite a while ago. If you think of how search engines find a website, it is based on keywords not nicely composed sentences. If the right keywords are there even as only a list, the page will be high among the search results.

And in the age of "fact-checking" and more how low-quality (and subject to financial interests) that can be, I would not be surprised many journalists using AI-generated content more and more in the future without actually checking how close it is to reality.

---

I did write your essay was thought-provoking, right? I hope it didn't provoke TOO MANY thoughts that I put into this comment :o)