The social architecture of Riken Yamamoto

Every day we’re losing the capacity to bridge differences and connect, but what can we do about it? Some ideas for designing a social future — from Riken Yamamoto to Rudolf Steiner.

What’s the purpose of a building? Is it merely functional? Is a house simply where we live? An office where we work? A store where we buy things?

Riken Yamamoto — the winner of this year’s Pritzker Prize, the “Nobel of architecture” — thinks it’s something more. He sees a building as a tension between social and antisocial forces, a balance between the public and private, the communal and the individual. Here’s how he describes it:

For me, to recognize space is to recognize an entire community. The current architectural approach emphasizes privacy, negating the necessity of societal relationships. However, we can still honor the freedom of each individual while living together in architectural space as a republic, fostering harmony across cultures and phases of life.

Society suffers when we don’t take this balance between “privacy” and “societal relationships” seriously. We become imbalanced — swinging too far onto the side of the antisocial. And that’s where we are today. We’re more isolated than ever (in fact, loneliness has become an “epidemic”). We’re less patient than ever (abandoning friends and family we consider “toxic”). And we have less goodwill than ever (we’re convinced that our political opponents are literally going to destroy the country, and maybe the world). We’ve become so individual and particular (and at times ego-maniacal) that it’s quite difficult to stand each other.

For Yamamoto, architecture is part of this problem: The buildings we create can push us farther apart, or bring us closer together, depending on their design.

Of course, architecture has not caused this extreme swing into the antisocial, but it can shed light on how we might counterbalance it. And there are other approaches as well, most notably described by the philosopher and social reformer — as well as occasional architect — Rudolf Steiner. We will explore all these approaches in what follows.

The tension between the public and the private began already in Yamamoto’s childhood home, where his mother ran a pharmacy out of the front of the house, while the family lived in back: “The threshold on one side was for family, and on the other side for community. I sat in between.”

His work as an architect can be seen as growing out of that experience, as an exploration of this “in between.”

In the modern world, we’re so quick to lock ourselves away, and our buildings largely encourage it. When we do finally leave those buildings, we take paths and roads that lead us to our next destination (often another building) as quickly as possible, as efficiently as possible. Which really means: with as few encounters as possible.

Yamamoto works against such impulses. He wants to encourage the possibility of interruption — of chance encounter. When he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the jury described his work as “multiplying opportunities for people to meet spontaneously.”

For example, his design of the Saitama Prefectural University connects two long, parallel buildings through a network of paths and patios that rise and fall over a patchwork of smaller buildings.

Such a landscape can look confusing, almost labyrinthine, but that’s part of what Yamamoto is exploring. His spaces blur the boundary between the public and the private; they bleed into each other.

He mixes up the rhythm of a space, separating and connecting things in unexpected ways. Where one would assume to find a single building, one might find a small village, or even a city.

His own home, which he calls Gazebo, is an example of this. Built on a rooftop, it provides separate dwelling places for a three-generation family, with sheltered decks linking them to one another, as well as to their neighbors and the outside world.

Another example is his design for the Future University of Hakodate, which consists of a single 5 story building, mostly made of glass, with large tiered platforms where students and teachers can gather, as well as smaller classrooms.

Of course this all raises the question, What should be private and what should be public? Is it a useful to sit in a class with glass walls, watching the clouds roll past? Does it connect you to the outside world, or just distract you? Or both?

One place where such transparency seems clearly beneficial is Yamamoto’s design of the Hiroshima Nishi Fire Station.

The work of firefighters is often veiled to the larger community (that is, unless you’re unfortunate enough to need them). But should it be? Wouldn’t it be better if the community was aware of what the firefighters were undertaking — day in and day out — on the community’s behalf?

Like so many of his buildings, Yamamoto’s fire station is mostly made of glass. And so the veil is removed; the firefighter’s work becomes transparent. What do people see when they visit? At the heart of the building is a training ground where visitors can watch firefighters drill and prepare.

In a very real sense, Yamamoto is less interested in the building itself, and more interested in what happens inside the building, because of the building. The material structure begins to melt, to disappear. What’s important is the space it creates, how it strengthens our social ties and counteracts our antisocial tendencies.

These ideas are closely related to those of the early 20th century social reformer Rudolf Steiner.

Steiner was keenly aware of how society is free-falling into the antisocial. But he made a crucial distinction: In itself, the antisocial isn’t actually a bad thing. Yes, it means we’re losing our social connections, but it’s because human beings are on a path towards greater and greater individuality. We’re becoming increasingly independent of one another, which also gives us the possibility of inner freedom, of developing ourselves to the full, of becoming ourselves and not just a member of a group.

But this necessary (and inevitable) march towards individuality also poses a danger: It can lead to the extremes of isolation, egotism, and selfishness if it isn’t counterbalanced, if we don’t also consciously develop our social nature. As Steiner describes it in his lecture “Social and Antisocial Forces”:

The antisocial forces must work inwardly so that human beings may reach the height of their development. Outwardly, in social life, structures must work so that people do not totally lose their outer connections in life…

The precise need of the future is that the social shall be brought to meet the antisocial in a systematic way.

So we find that socially-minded design, including architecture, is an essential need of the present-day.

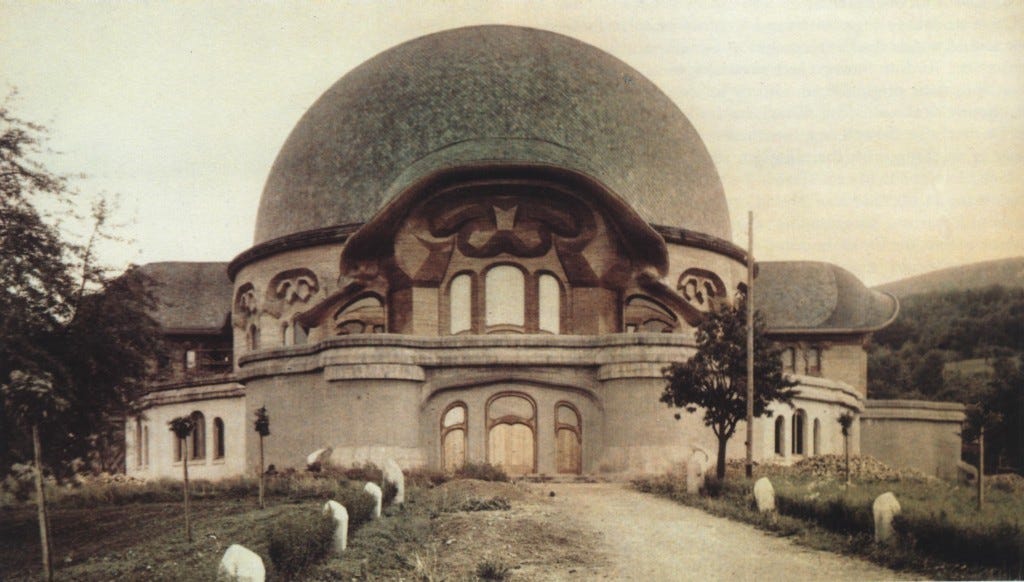

In terms of his own architecture, there is a story about Steiner disagreeing with one of his assistants on the First Goetheanum — a building he created with a theater and lecture hall at its center. The assistant thought Steiner’s design for the coat room was flawed. Instead of people hanging up their coats and going directly into the hall, they’d have to double-back and push their way through a crowd of people who were also arriving to hang up their coats.

The story goes that Steiner ended their morning meeting with the issue unresolved, and both of them went their separate ways. But as the morning continued, the assistant noticed that Steiner was constantly going out of his way to come greet him — for example, they’d be on different sides of the building site and Steiner would leave whatever he was doing to come talk to him. Again, at lunch, Steiner went out of his way to come see him, but now he said something like, “Sir, you must have noticed how much effort I’ve had to make in order to cross paths with you all morning. Truly, it’s not so easy to simply run into each other — it’s not so easy to be social! So why would we want to make it even more difficult by smoothly funneling everyone into the hall after they’ve hung up their coats, instead of giving them the opportunity to naturally run into each other and exchange a few words?”

This is merely one example, but Steiner’s description of the need for social “structures” so that “people do not totally lose their outer connections” was certainly not limited to architecture. As he said, “The precise need of the future is that the social shall be brought to meet the antisocial in a systematic way” — and he meant this in every area of life!

For example, Steiner saw the structure of companies as both social and antisocial. Very often a business starts with a social impulse. An entrepreneur wants to meet some need in the community — they want to start a cafe where folks can gather, or make outdoor equipment that encourages people to connect with nature. But over time that ideal can be lost, can become solely about personal gain, especially when the entrepreneur gives the company to their kids or sells it to the highest bidder or goes public (selling its shares on the stock market, and thereby making its highest legal obligation the maximization of shareholder value). In these ways it becomes antisocial.

So how can a company stay social? Steiner described a form of ownership that was private in nature, but still socially-focused. He described that when the initial entrepreneur no longer wants to serve the community, the ownership shouldn’t be allowed to fall into the hands of someone who wants to exploit it for their own benefit, but should be transferred to someone who also wants to serve the community. He described this not as “private” or “public” ownership, but as “circulating” ownership — ownership that moves from person to person, but always to someone with a social impulse and the capacity to carry it out. Here’s how he put it in his book The Social Future:

The transference of a business concern… is a matter of transfer from the capable to the capable, from those who can work in the service of the community to those who can also work in the best way for the common good. On this kind of transference the social safety of the future depends.

This can sound naive, but people are already doing it. “Steward ownership” is one expression of this idea which is quickly gaining traction in Europe and America (check out this great TedX talk about it), and I’ve written about other models.

And when you stop to think of it, Why would we ever make ownership laws that allow our shared resources to fall into the hands of the incompetent or antisocial? Why would we imagine someone’s wealth to be any sort of indicator of their capacities or their desire to serve society? Isn’t that a bit naive? Why not just pay attention to a person’s actual capacities?

Although Steiner’s understanding of the balance between the social and antisocial goes much farther than just architecture, it’s interesting to come back to one more similarity between Steiner’s and Yamamoto’s architectural work.

As we saw, Yamamoto’s work begins to disappear in both a literal and a figurative sense. Through his use of glass, his buildings become actually transparent, and by focusing on what happens inside the buildings, and less on the buildings themselves, they also become transparent in a different sense. They become more about an activity and less about a thing. They lose something of their noun quality, and become more like a verb. As Yamamoto describes it:

Architecture should be something that serves as a background for life, not something that overshadows it. The real value of architecture is found in the spaces it shapes, not just the structure itself.

Steiner also understood the nature of architecture — and really all art — in this way. Here’s how he describes the First Goetheanum:

Our building is built on the principle of a [cake mold]. Imagine you have a tin mold and you bake your cake in it. Which is more important — the mold or the cake? Obviously the cake….

Similarly, in our building it is not the surrounding walls that are of importance, it is what is enclosed within the surrounding walls. And within the walls will be the feelings and thoughts of the people who are in the building… The mold has to be of such a kind that it leads to the development of right thoughts and right feelings. This is the principle underlying the new art, in contrast to the art of olden times. In the art of olden times the essential thing was what is outside in space; but in the new art something else is of account. What is outside is no more than the mold, and the essential thing cannot really be created by the artist at all, it is what is within.

Nor is this true only of plastic forms. It is equally true of painting. The important thing is not what is painted, but the experience in feeling to which the painting gives rise. Painting too is no more than a cake mold!

This clarifies things still further. The most important thing is not the activity that happens in a space. The most important thing is the activity that happens in us — the thoughts and feelings that arise when we’re in a building, or looking at a painting. We need to be asking ourselves, How is it different to stand in a church than to stand in a warehouse? What is the difference in feeling? Where do our thoughts go?

From this perspective, it’s not actually the physical building or painting that really matters. What matters is what happens in our consciousness. And ultimately, it’s in the realm of consciousness where the social resides as well. It is not really about us bumping into one another in outer life, having more opportunities to meet and discuss things. Those things are important, but what’s most important is how we evolve our thoughts and feelings towards each other, how we feel ourselves connected to one another, how we come to take an interest in another person, how we carry that person within us.

It is this immaterial social and spiritual substance that we need to learn to become sensitive to. And it’s this that Yamamoto and Steiner explore in their work. This is the real substance of human connection and, in the end, this is what will enable us to find a bridge back to one another, to overcome all the individual and particular differences that separate us.

It has been a while since I considered architecture, so this was really refreshing for me - especially the topic you presented, tying it to the social issue, to Steiner and the Goetheanum. It gave rise to a feeling of enthusiasm at a time when, as you rightly say, we live in a state of loneliness and separation - both outwardly and as an inner state. Very refreshing - nutritious food for thought!

We need to be reminded about what matters and provoked to think creatively - all the time. And you are doing that with your work. Otherwise something inside us withers and our imagination wanes. Your article made me think of that as well.

I appreciate your parallel of architectural design in promoting a stronger social engagement. I will say, however, that I wish it were that easy, (although I also realize you are not contending that it is). It seems as though even when we have occasion to come away from behind our screens and out of our homes to see and be with each other, we still find ourselves alone and lacking union with each other. How do we counter this strong power that has us at odds with our dearest family members - our children, parents, closest friends? I feel we're being played - and we're not doing well. Our time is not so different from Steiner's time in ways of political poles. In addressing ideas like Marxism or spiritual science, he makes the following observations: "One can therefore prove something quite strictly, and also prove its opposite. It is possible today to prove spiritualism on the one hand and materialism on the other. And people may fight against each other from equally good standpoints because present-day intellectualism is in an upper layer of reality and does not go down into the depths of being. And it is the same with party opinions. A man who does not look deeper but simply lets himself be accepted into a certain party-circle — by reason of his education, heredity, circumstances of life and State — quite honestly believes — or so he thinks — in the possibility of proving the tenets of the party into which he has slipped, as he says. And then — then he fights against someone else who has slipped into another party! And the one is just as right as the other." (Ahrimanic Deception, Oct. 27, 1919).

In circles where I go to find support for the same spiritual thoughts and longings that I have, I find myself recently discouraged and disheartened at the division that shows itself in political bias (within these circles), - Trump, Biden, Israel, Palestine, to vaccinate, to not vaccinate, freedom to abort, protection of life, etc..... You mention towards the end of your essay "what’s most important is how we evolve our thoughts and feelings towards each other, how we feel ourselves connected to one another, how we come to take an interest in another person, how we carry that person within us." I so agree with this. And yet, we, (or at least me), still struggle in fighting that emotion that causes paralysis in moving forward with another when such issues loom so big for all of us. How do we release these issues placed in front of us in order to secure our connection to each other and stop seeing each other as "toxic"?